congenital heart disease

Snapshots of Life: Green Eggs and Heart Valves

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

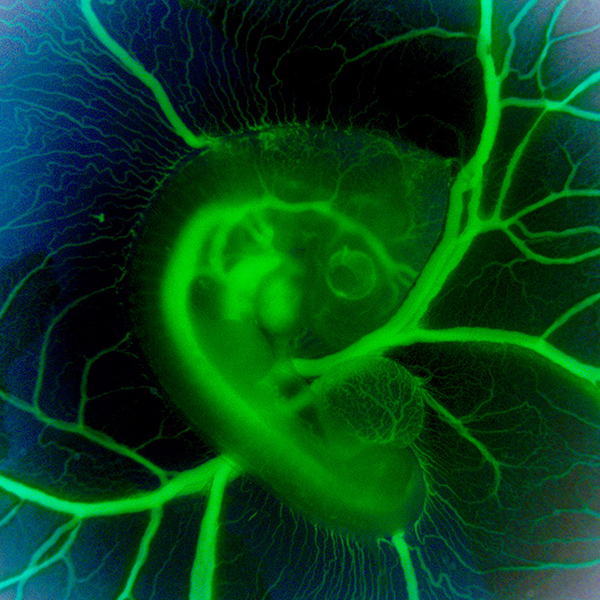

What might appear in this picture to be an exotic, green glow worm served up on a collard leaf actually comes from something we all know well: an egg. It’s a 3-day-old chicken embryo that’s been carefully removed from its shell, placed in a special nutrient-rich bath to keep it alive, and then photographed through a customized stereo microscope. In the middle of the image, just above the blood vessels branching upward, you can see the outline of a transparent, developing eye. Directly to the left is the embryonic heart, which at this early stage is just a looped tube not yet with valves or pumping chambers.

Developing chicks are one of the most user-friendly models for studying normal and abnormal heart development. Human and chick hearts have a lot in common structurally, with four chambers and four valves pumping two circulations of blood in parallel. Unlike mammalian embryos tucked away in the womb, researchers have free range to study the chick heart in or out of the egg as it develops from a simple looped tube to a four-chambered organ.

Jonathan Butcher and his NIH-supported research group at Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, snapped this photo, a winner in the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology’s 2015 BioArt competition, to monitor differences in blood flow through the developing chick heart. You can get a sense of these differences by the varying intensities of green fluorescence in the blood vessels. The Butcher lab is interested in understanding how the force of the blood flow triggers the switching on and off of genes responsible for making functional heart valves. Although the four valves aren’t yet visible in this image, they will soon elongate into flap-like structures that open and close to begin regulating the normal flow of blood through the heart.

LabTV: Curious About Heart Failure in Young Children

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Growing up in Pittsburgh, Josh Maxwell enjoyed romping around outdoors. He was an adventurous kid who liked to catch live frogs and snakes, lug them home, and surprise his parents with the latest creepy find. Maxwell rode his curiosity for nature to a bachelor’s degree in biology from Allegheny College, Meadville, PA. He then went on to earn a Ph.D. in cell and molecular physiology from Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine.

Maxwell, the focus of our latest LabTV video, is now a research scientist in the lab of Michael Davis at Emory University, Atlanta, where he studies pediatric heart failure. Maxwell grows cardiac cells in tissue culture and tries to fix the defects that lie within. What’s driving this important research is that a heart transplant remains the only option to save the lives of many kids born with severe congenital heart problems. In addition to shortages of donated organs, undergoing such a major operation at such a tender age can take a real toll on the children and their families. Maxwell wants to be a part of discovering non-surgical alternatives to regenerate cardiac tissue and one day repair a damaged heart for a lifetime.