cell biology

The Perfect Cytoskeletal Storm

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Ever thought about giving cell biology a whirl? If so, I suggest you sit down and take a look at this full-blown cytoskeletal “storm,” which provides a spectacular dynamic view of the choreography of life.

Before a cell divides, it undergoes a process called mitosis that copies its chromosomes and produces two identical nuclei. As part of this process, microtubules, which are structural proteins that help make up the cell’s cytoskeleton, reorganize the newly copied chromosomes into a dense, football-shaped spindle. The position of this mitotic spindle tells the cell where to divide, allowing each daughter cell to contain its own identical set of DNA.

To gain a more detailed view of microtubules in action, researchers designed an experimental system that utilizes an extract of cells from the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis). As the video begins, a star-like array of microtubules (red) radiate outward in an apparent effort to prepare for cell division. In this configuration, the microtubules continually adjust their lengths with the help of the protein EB-1 (green) at their tips. As the microtubules grow and bump into the walls of a lab-generated, jelly-textured enclosure (dark outline), they buckle—and the whole array then whirls around the center.

Abdullah Bashar Sami, a Ph.D. student in the NIH-supported lab of Jesse “Jay” Gatlin, University of Wyoming, Laramie, shot this movie as a part his basic research to explore the still poorly understood physical forces generated by microtubules. The movie won first place in the 2019 Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest sponsored by the American Society for Cell Biology. The contest honors the 25th anniversary of the discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP), which transformed cell biology and earned the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for three scientists who had been supported by NIH.

Like many movies, the setting was key to this video’s success. The video was shot inside a microfluidic chamber, designed in the Gatlin lab, to study the physics of microtubule assembly just before cells divide. The tiny chamber holds a liquid droplet filled with the cell extract.

When the liquid is exposed to an ultra-thin beam of light, it forms a jelly-textured wall, which traps the molecular contents inside [1]. Then, using time-lapse microscopy, the researchers watch the mechanical behavior of GFP-labeled microtubules [2] to see how they work to position the mitotic spindle. To do this, microtubules act like shapeshifters—scaling to adjust to differences in cell size and geometry.

The Gatlin lab is continuing to use their X. laevis system to ask fundamental questions about microtubule assembly. For many decades, both GFP and this amphibian model have provided cell biologists with important insights into the choreography of life, and, as this work shows, we can expect much more to come!

References:

[1] Microtubule growth rates are sensitive to global and local changes in microtubule plus-end density. Geisterfer ZM, Zhu D, Mitchison T, Oakey J, Gatlin JC. November 20, 2019.

[2] Tau-based fluorescent protein fusions to visualize microtubules. Mooney P, Sulerud T, Pelletier JF, Dilsaver MR, et al. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 2017 Jun;74(6):221-232.

Links:

Mitosis (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Gatlin Lab (University of Wyoming, Laramie)

Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest (American Society for Cell Biology, Bethesda, MD)

2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (Nobel Foundation, Stockholm, Sweden)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Seeing the Cytoskeleton in a Whole New Light

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s been 25 years since researchers coaxed a bacterium to synthesize an unusual jellyfish protein that fluoresced bright green when irradiated with blue light. Within months, another group had also fused this small green fluorescent protein (GFP) to larger proteins to make their whereabouts inside the cell come to light—like never before.

To mark the anniversary of this Nobel Prize-winning work and show off the rainbow of color that is now being used to illuminate the inner workings of the cell, the American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB) recently held its Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest. Over the next few months, my blog will feature some of the most eye-catching entries—starting with this video that will remind those who grew up in the 1980s of those plasma balls that, when touched, light up with a simulated bolt of colorful lightning.

This video, which took third place in the ASCB contest, shows the cytoskeleton of a frequently studied human breast cancer cell line. The cytoskeleton is made from protein structures called microtubules, made visible by fluorescently tagging a protein called doublecortin (orange). Filaments of another protein called actin (purple) are seen here as the fine meshwork in the cell periphery.

The cytoskeleton plays an important role in giving cells shape and structure. But it also allows a cell to move and divide. Indeed, the motion in this video shows that the complex network of cytoskeletal components is constantly being organized and reorganized in ways that researchers are still working hard to understand.

Jeffrey van Haren, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, shot this video using the tools of fluorescence microscopy when he was a postdoctoral researcher in the NIH-funded lab of Torsten Wittman, University of California, San Francisco.

All good movies have unusual plot twists, and that’s truly the case here. Though the researchers are using a breast cancer cell line, their primary interest is in the doublecortin protein, which is normally found in association with microtubules in the developing brain. In fact, in people with mutations in the gene that encodes this protein, neurons fail to migrate properly during development. The resulting condition, called lissencephaly, leads to epilepsy, cognitive disability, and other neurological problems.

Cancer cells don’t usually express doublecortin. But, in some of their initial studies, the Wittman team thought it would be much easier to visualize and study doublecortin in the cancer cells. And so, the researchers tagged doublecortin with an orange fluorescent protein, engineered its expression in the breast cancer cells, and van Haren started taking pictures.

This movie and others helped lead to the intriguing discovery that doublecortin binds to microtubules in some places and not others [1]. It appears to do so based on the ability to recognize and bind to certain microtubule geometries. The researchers have since moved on to studies in cultured neurons.

This video is certainly a good example of the illuminating power of fluorescent proteins: enabling us to see cells and their cytoskeletons as incredibly dynamic, constantly moving entities. And, if you’d like to see much more where this came from, consider visiting van Haren’s Twitter gallery of microtubule videos here:

Reference:

[1] Doublecortin is excluded from growing microtubule ends and recognizes the GDP-microtubule lattice. Ettinger A, van Haren J, Ribeiro SA, Wittmann T. Curr Biol. 2016 Jun 20;26(12):1549-1555.

Links:

Lissencephaly Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Wittman Lab (University of California, San Francisco)

Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest (American Society for Cell Biology, Bethesda, MD)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Defining Neurons in Technicolor

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Can you identify a familiar pattern in this image’s square grid? Yes, it’s the outline of the periodic table! But instead of organizing chemical elements, this periodic table sorts 46 different types of neurons present in the visual cortex of a mouse brain.

Scientists, led by Hongkui Zeng at the Allen Institute for Brain Science, Seattle, constructed this periodic table by assigning colors to their neuronal discoveries based upon their main cell functions [1]. Cells in pinks, violets, reds, and oranges have inhibitory electrical activity, while those in greens and blues have excitatory electrical activity.

For any given cell, the darker colors indicate dendrites, which receive signals from other neurons. The lighter colors indicate axons, which transmit signals. Examples of electrical properties—the number and intensity of their “spikes”—appear along the edges of the table near the bottom.

To create this visually arresting image, Zeng’s NIH-supported team injected dye-containing probes into neurons. The probes are engineered to carry genes that make certain types of neurons glow bright colors under the microscope.

This allowed the researchers to examine a tiny slice of brain tissue and view each colored neuron’s shape, as well as measure its electrical response. They followed up with computational tools to combine these two characteristics and classify cell types based on their shape and electrical activity. Zeng’s team could then sort the cells into clusters using a computer algorithm to avoid potential human bias from visually interpreting the data.

Why compile such a detailed atlas of neuronal subtypes? Although scientists have been surveying cells since the invention of the microscope centuries ago, there is still no consensus on what a “cell type” is. Large, rich datasets like this atlas contain massive amounts of information to characterize individual cells well beyond their appearance under a microscope, helping to explain factors that make cells similar or dissimilar. Those differences may not be apparent to the naked eye.

Just last year, Allen Institute researchers conducted similar work by categorizing nearly 24,000 cells from the brain’s visual and motor cortex into different types based upon their gene activity [2]. The latest research lines up well with the cell subclasses and types categorized in the previous gene-activity work. As a result, the scientists have more evidence that each of the 46 cell types is actually distinct from the others and likely drives a particular function within the visual cortex.

Publicly available resources, like this database of cell types, fuel much more discovery. Scientists all over the world can look at this table (and soon, more atlases from other parts of the brain) to see where a cell type fits into a region of interest and how it might behave in a range of brain conditions.

References:

[1] Classification of electrophysiological and morphological neuron types in the mouse visual cortex. N Gouwens NW, et al. Neurosci. 2019 Jul;22(7):1182-1195.

[2] Shared and distinct transcriptomic cell types across neocortical areas. Tasic B, et al. Nature. 2018 Nov;563(7729):72-78.

Links:

Brain Basics: The Life and Death of a Neuron (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Cell Types: Overview of the Data (Allen Brain Atlas/Allen Institute for Brain Science, Seattle)

Hongkui Zeng (Allen Institute)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development

Caught on Video: Cancer Cells in Act of Cannibalism

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Tumors rely on a variety of tricks to grow, spread, and resist our best attempts to destroy them. Now comes word of yet another of cancer’s surprising stunts: when chemotherapy treatment hits hard, some cancer cells survive by cannibalizing other cancer cells.

Researchers recently caught this ghoulish behavior on video. In what, during this Halloween season, might look a little bit like The Blob, you can see a down-for-the-count breast cancer cell (green), treated earlier with the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin, gobbling up a neighboring cancer cell (red). The surviving cell delivers its meal to internal compartments called lysosomes, which digest it in a last-ditch effort to get some nourishment and keep going despite what should have been a lethal dose of a cancer drug.

Crystal Tonnessen-Murray, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of James Jackson, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, captured these dramatic interactions using time-lapse and confocal microscopy. When Tonnessen-Murray saw the action, she almost couldn’t believe her eyes. Tumor cells eating tumor cells wasn’t something that she’d learned about in school.

As the NIH-funded team described in the Journal of Cell Biology, these chemotherapy-treated breast cancer cells were not only cannibalizing their neighbors, they were doing it with remarkable frequency [1]. But why?

A possible explanation is that some cancer cells resist chemotherapy by going dormant and not dividing. The new study suggests that while in this dormant state, cannibalism is one way that tumor cells can keep going.

The study also found that these acts of cancer cell cannibalism depend on genetic programs closely resembling those of immune cells called macrophages. These scavenging cells perform their important protective roles by gobbling up invading bacteria, viruses, and other infectious microbes. Drug-resistant breast cancer cells have apparently co-opted similar programs in response to chemotherapy but, in this case, to eat their own neighbors.

Tonnessen-Murray’s team confirmed that cannibalizing cancer cells have a survival advantage. The findings suggest that treatments designed to block the cells’ cannibalistic tendencies might hold promise as a new way to treat otherwise hard-to-treat cancers. That’s a possibility the researchers are now exploring, although they report that stopping the cells from this dramatic survival act remains difficult.

Reference:

[1] Chemotherapy-induced senescent cancer cells engulf other cells to enhance their survival. Tonnessen-Murray CA, Frey WD, Rao SG, Shahbandi A, Ungerleider NA, Olayiwola JO, Murray LB, Vinson BT, Chrisey DB, Lord CJ, Jackson JG. J Cell Biol. 2019 Sep 17.

Links:

Breast Cancer (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

James Jackson (Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

These Oddball Cells May Explain How Influenza Leads to Asthma

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most people who get the flu bounce right back in a week or two. But, for others, the respiratory infection is the beginning of lasting asthma-like symptoms. Though I had a flu shot, I had a pretty bad respiratory illness last fall, and since that time I’ve had exercise-induced asthma that has occasionally required an inhaler for treatment. What’s going on? An NIH-funded team now has evidence from mouse studies that such long-term consequences stem in part from a surprising source: previously unknown lung cells closely resembling those found in taste buds.

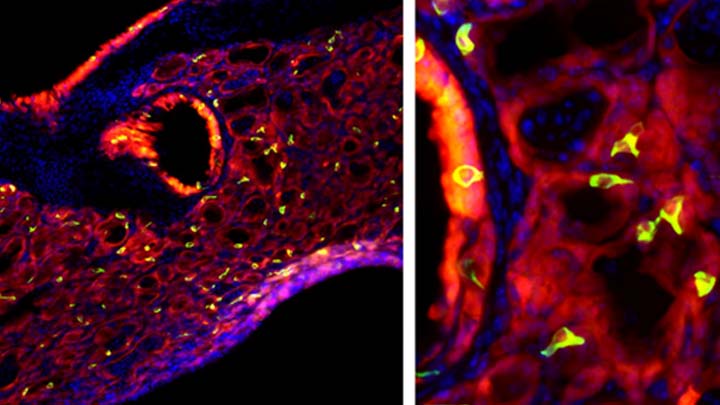

The image above shows the lungs of a mouse after a severe case of H1N1 influenza infection, a common type of seasonal flu. Notice the oddball cells (green) known as solitary chemosensory cells (SCCs). Those little-known cells display the very same chemical-sensing surface proteins found on the tongue, where they allow us to sense bitterness. What makes these images so interesting is, prior to infection, the healthy mouse lungs had no SCCs.

SCCs, sometimes called “tuft cells” or “brush cells” or “type II taste receptor cells”, were first described in the 1920s when a scientist noticed unusual looking cells in the intestinal lining [1] Over the years, such cells turned up in the epithelial linings of many parts of the body, including the pancreas, gallbladder, and nasal passages. Only much more recently did scientists realize that those cells were all essentially the same cell type. Owing to their sensory abilities, these epithelial cells act as a kind of lookout for signs of infection or injury.

This latest work on SCCs, published recently in the American Journal of Physiology–Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, adds to this understanding. It comes from a research team led by Andrew Vaughan, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia [2].

As a post-doc, Vaughan and colleagues had discovered a new class of cells, called lineage-negative epithelial progenitors, that are involved in abnormal remodeling and regrowth of lung tissue after a serious respiratory infection [3]. Upon closer inspection, they noticed that the remodeling of lung tissue post-infection often was accompanied by sustained inflammation. What they didn’t know was why.

The team, including Noam Cohen of Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine and De’Broski Herbert, also of Penn Vet, noticed signs of an inflammatory immune response several weeks after an influenza infection. Such a response in other parts of the body is often associated with allergies and asthma. All were known to involve SCCs, and this begged the question: were SCCs also present in the lungs?

Further work showed not only were SCCs present in the lungs post-infection, they were interspersed across the tissue lining. When the researchers exposed the animals’ lungs to bitter compounds, the activated SCCs multiplied and triggered acute inflammation.

Vaughan’s team also found out something pretty cool. The SCCs arise from the very same lineage of epithelial progenitor cells that Vaughan had discovered as a post-doc. These progenitor cells produce cells involved in remodeling and repair of lung tissue after a serious lung infection.

Of course, mice aren’t people. The researchers now plan to look in human lung samples to confirm the presence of these cells following respiratory infections.

If confirmed, the new findings might help to explain why kids who acquire severe respiratory infections early in life are at greater risk of developing asthma. They suggest that treatments designed to control these SCCs might help to treat or perhaps even prevent lifelong respiratory problems. The hope is that ultimately it will help to keep more people breathing easier after a severe bout with the flu.

References:

[1] Closing in on a century-old mystery, scientists are figuring out what the body’s ‘tuft cells’ do. Leslie M. Science. 2019 Mar 28.

[2] Development of solitary chemosensory cells in the distal lung after severe influenza injury. Rane CK, Jackson SR, Pastore CF, Zhao G, Weiner AI, Patel NN, Herbert DR, Cohen NA, Vaughan AE. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019 Mar 25.

[3] Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Vaughan AE, Brumwell AN, Xi Y, Gotts JE, Brownfield DG, Treutlein B, Tan K, Tan V, Liu FC, Looney MR, Matthay MA, Rock JR, Chapman HA. Nature. 2015 Jan 29;517(7536):621-625.

Links:

Asthma (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Influenza (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Vaughan Lab (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Cohen Lab (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Herbert Lab (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

Mood-Altering Messenger Goes Nuclear

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Serotonin is best known for its role as a chemical messenger in the brain, helping to regulate mood, appetite, sleep, and many other functions. It exerts these influences by binding to its receptor on the surface of neural cells. But startling new work suggests the impact of serotonin does not end there: the molecule also can enter a cell’s nucleus and directly switch on genes.

While much more study is needed, this is a potentially groundbreaking discovery. Not only could it have implications for managing depression and other mood disorders, it may also open new avenues for treating substance abuse and neurodegenerative diseases.

To understand how serotonin contributes to switching genes on and off, a lesson on epigenetics is helpful. Keep in mind that the DNA instruction book of all cells is essentially the same, yet the chapters of the book are read in very different ways by cells in different parts of the body. Epigenetics refers to chemical marks on DNA itself or on the protein “spools” called histones that package DNA. These marks influence the activity of genes in a particular cell without changing the underlying DNA sequence, switching them on and off or acting as “volume knobs” to turn the activity of particular genes up or down.

The marks include various chemical groups—including acetyl, phosphate, or methyl—which are added at precise locations to those spool-like proteins called histones. The addition of such groups alters the accessibility of the DNA for copying into messenger RNA and producing needed proteins.

In the study reported in Nature, researchers led by Ian Maze and postdoctoral researcher Lorna Farrelly, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, followed a hunch that serotonin molecules might also get added to histones [1]. There had been hints that it might be possible. For instance, earlier evidence suggested that inside cells, serotonin could enter the nucleus. There also was evidence that serotonin could attach to proteins outside the nucleus in a process called serotonylation.

These data begged the question: Is serotonylation important in the brain and/or other living tissues that produce serotonin in vivo? After a lot of hard work, the answer now appears to be yes.

These NIH-supported researchers found that serotonylation does indeed occur in the cell nucleus. They also identified a particular enzyme that directly attaches serotonin molecules to histone proteins. With serotonin attached, DNA loosens on its spool, allowing for increased gene expression.

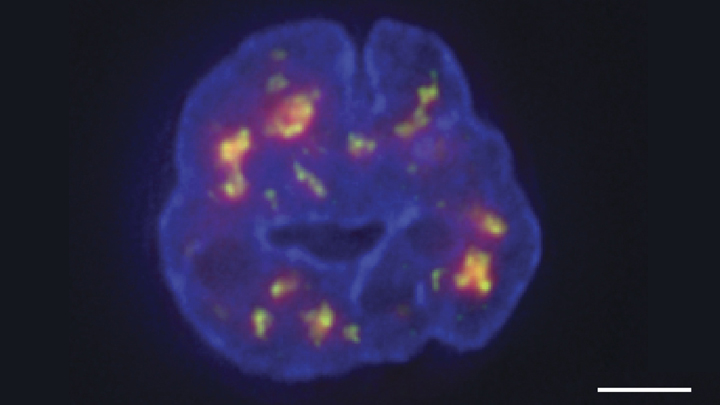

The team found that histone serotonylation takes place in serotonin-producing human neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). They also observed this process occurring in the brains of developing mice.

In fact, the researchers found evidence of those serotonin marks in many parts of the body. They are especially prevalent in the brain and gut, where serotonin also is produced in significant amounts. Those marks consistently correlate with areas of active gene expression.

The serotonin mark often occurs on histones in combination with a second methyl mark. The researchers suggest that this double marking of histones might help to further reinforce an active state of gene expression.

This work demonstrates that serotonin can directly influence gene expression in a manner that’s wholly separate from its previously known role in transmitting chemical messages from one neuron to the next. And, there are likely other surprises in store.

The newly discovered role of serotonin in modifying gene expression may contribute significantly to our understanding of mood disorders and other psychiatric conditions with known links to serotonin signals, suggesting potentially new targets for therapeutic intervention. But for now, this fundamental discovery raises many more intriguing questions than it answers.

Science is full of surprises, and this paper is definitely one of them. Will this kind of histone marking occur with other chemical messengers, such as dopamine and acetylcholine? This unexpected discovery now allows us to track serotonin and perhaps some of the brain’s other chemical messengers to see what they might be doing in the cell nucleus and whether this information might one day help in treating the millions of Americans with mood and behavioral disorders.

Reference:

[1] Histone serotonylation is a permissive modification that enhances TFIID binding to H3K4me3. Farrelly LA, Thompson RE, Zhao S, Lepack AE, Lyu Y, Bhanu NV, Zhang B, Loh YE, Ramakrishnan A, Vadodaria KC, Heard KJ, Erikson G, Nakadai T, Bastle RM, Lukasak BJ, Zebroski H 3rd, Alenina N, Bader M, Berton O, Roeder RG, Molina H, Gage FH, Shen L, Garcia BA, Li H, Muir TW, Maze I. Nature. 2019 Mar 13. [Epub ahead of print]

Links:

Any Mood Disorder (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction (National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH)

Epigenomics (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Maze Lab (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY)

NIH Support: National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute

Biomedical Research Highlighted in Science’s 2018 Breakthroughs

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A Happy New Year to one and all! While many of us were busy wrapping presents, the journal Science announced its much-anticipated scientific breakthroughs of 2018. In case you missed the announcement [1], it was another banner year for the biomedical sciences.

The 2018 Breakthrough of the Year went to biomedical science and its ability to track the development of life—one cell at a time—in a variety of model organisms. This newfound ability opens opportunities to understand the biological basis of life more systematically than ever before. Among Science’s “runner-up” breakthroughs, more than half had strong ties to the biomedical sciences and NIH-supported research.

Sound intriguing? Let’s take a closer look at some of the amazing science conducted in 2018, starting with Science’s Breakthrough of the Year.

Development Cell by Cell: For millennia, biologists have wondered how a single cell develops into a complete multicellular organism, such as a frog or a mouse. But solving that mystery was almost impossible without the needed tools to study development systematically, one cell at a time. That’s finally started to change within the last decade. I’ve highlighted the emergence of some of these powerful tools on my blog and the interesting ways that they were being applied to study development.

Over the past few years, all of this technological progress has come to a head. Researchers, many of them NIH-supported, used sophisticated cell labeling techniques, nucleic acid sequencing, and computational strategies to isolate thousands of cells from developing organisms, sequence their genetic material, and determine their location within that developing organism.

In 2018 alone, groundbreaking single-cell analysis papers were published that sequentially tracked the 20-plus cell types that arise from a fertilized zebrafish egg, the early formation of organs in a frog, and even the creation of a new limb in the Axolotl salamander. This is just the start of amazing discoveries that will help to inform us of the steps, or sometimes missteps, within human development—and suggest the best ways to prevent the missteps. In fact, efforts are now underway to gain this detailed information in people, cell by cell, including the international Human Cell Atlas and the NIH-supported Human BioMolecular Atlas Program.

An RNA Drug Enters the Clinic: Twenty years ago, researchers Andrew Fire and Craig Mello showed that certain small, noncoding RNA molecules can selectively block genes in our cells from turning “on” through a process called RNA interference (RNAi). This work, for the which these NIH grantees received the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, soon sparked a wave of commercial interest in various noncoding RNA molecules for their potential to silence the expression of a disease-causing gene.

After much hard work, the first gene-silencing RNA drug finally came to market in 2018. It’s called Onpattro™ (patisiran), and the drug uses RNAi to treat the peripheral nerve disease that can afflict adults with a rare disease called hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. This hard-won success may spark further development of this novel class of biopharmaceuticals to treat a variety of conditions, from cancer to cardiovascular disorders, with potentially greater precision.

Rapid Chemical Structure Determination: Last October, two research teams released papers almost simultaneously that described an incredibly fast new imaging technique to determine the structure of smaller organic chemical compounds, or “small molecules“ at atomic resolution. Small molecules are essential components of molecular biology, pharmacology, and drug development. In fact, most of our current medicines are small molecules.

News of these papers had many researchers buzzing, and I highlighted one of them on my blog. It described a technique called microcrystal electron diffraction, or MicroED. It enabled these NIH-supported researchers to take a powder form of small molecules (progesterone was one example) and generate high-resolution data on their chemical structures in less than a half-hour! The ease and speed of MicroED could revolutionize not only how researchers study various disease processes, but aid in pinpointing which of the vast number of small molecules can become successful therapeutics.

How Cells Marshal Their Contents: About a decade ago, researchers discovered that many proteins in our cells, especially when stressed, condense into circumscribed aqueous droplets. This so-called phase separation allows proteins to gather in higher concentrations and promote reactions with other proteins. The NIH soon began supporting several research teams in their groundbreaking efforts to explore the effects of phase separation on cell biology.

Over the past few years, work on phase separation has taken off. The research suggests that this phenomenon is critical in compartmentalizing chemical reactions within the cell without the need of partitioning membranes. In 2018 alone, several major papers were published, and the progress already has some suggesting that phase separation is not only a basic organizing principle of the cell, it’s one of the major recent breakthroughs in biology.

Forensic Genealogy Comes of Age: Last April, police in Sacramento, CA announced that they had arrested a suspect in the decades-long hunt for the notorious Golden State Killer. As exciting as the news was, doubly interesting was how they caught the accused killer. The police had the Golden Gate Killer’s DNA, but they couldn’t determine his identity, that is, until they got a hit on a DNA profile uploaded by one of his relatives to a public genealogy database.

Though forensic genealogy falls a little outside of our mission, NIH has helped to advance the gathering of family histories and using DNA to study genealogy. In fact, my blog featured NIH-supported work that succeeded in crowdsourcing 600 years of human history.

The researchers, using the online profiles of 86 million genealogy hobbyists with their permission, assembled more than 5 million family trees. The largest totaled more than 13 million people! By merging each tree from the crowd-sourced and public data, they were able to go back about 11 generations—to the 15th century and the days of Christopher Columbus. Though they may not have caught an accused killer, these large datasets provided some novel insights into our family structures, genes, and longevity.

An Ancient Human Hybrid: Every year, researchers excavate thousands of bone fragments from the remote Denisova Cave in Siberia. One such find would later be called Denisova 11, or “Denny” for short.

Oh, what a fascinating genomic tale Denny’s sliver of bone had to tell. Denny was at least 13 years old and lived in Siberia roughly 90,000 years ago. A few years ago, an international research team found that DNA from the mitochondria in Denny’s cells came from a Neanderthal, an extinct human relative.

In 2018, Denny’s family tree got even more interesting. The team published new data showing that Denny was female and, more importantly, she was a first generation mix of a Neanderthal mother and a father who belonged to another extinct human relative called the Denisovans. The Denisovans, by the way, are the first human relatives characterized almost completely on the basis of genomics. They diverged from Neanderthals about 390,000 years ago. Until about 40,000 years ago, the two occupied the Eurasian continent—Neanderthals to the west, and Denisovans to the east.

Denny’s unique genealogy makes her the first direct descendant ever discovered of two different groups of early humans. While NIH didn’t directly support this research, the sequencing of the Neanderthal genome provided an essential resource.

As exciting as these breakthroughs are, they only scratch the surface of ongoing progress in biomedical research. Every field of science is generating compelling breakthroughs filled with hope and the promise to improve the lives of millions of Americans. So let’s get started with 2019 and finish out this decade with more truly amazing science!

Reference:

[1] “2018 Breakthrough of the Year,” Science, 21 December 2018.

NIH Support: These breakthroughs represent the culmination of years of research involving many investigators and the support of multiple NIH institutes.

Building a 3D Map of the Genome

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Chen et al., 2018

Researchers have learned a lot in recent years about how six-plus feet of human DNA gets carefully packed into a tiny cell nucleus that measures less than .00024 of an inch. Under those cramped conditions, we’ve been learning more and more about how DNA twists, turns, and spatially orients its thousands of genes within the nucleus and what this positioning might mean for health and disease.

Thanks to a new technique developed by an NIH-funded research team, there is now an even more refined view [1]. The image above features the nucleus (blue) of a human leukemia cell. The diffuse orange-red clouds highlight chemically labeled DNA found in close proximity to the tiny nuclear speckles (green). You’ll need to look real carefully to see the nuclear speckles, but these structural landmarks in the nucleus have long been thought to serve as storage sites for important cellular machinery.

A Tribute to Robert Goldman

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

My lab has had a wonderfully productive collaboration with Robert Goldman at Northwestern University, Chicago. On September 25, 2018, Northwestern honored him at a celebratory symposium. Though I couldn’t attend the event, it was my pleasure to record this musical tribute to such a fantastic cell biologist. Credit: Wally Akinso

A Ray of Molecular Beauty from Cryo-EM

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Subramaniam Lab, National Cancer Institute, NIH

Walk into a dark room, and it takes a minute to make out the objects, from the wallet on the table to the sleeping dog on the floor. But after a few seconds, our eyes are able to adjust and see in the near-dark, thanks to a protein called rhodopsin found at the surface of certain specialized cells in the retina, the thin, vision-initiating tissue that lines the back of the eye.

This illustration shows light-activating rhodopsin (orange). The light photons cause the activated form of rhodopsin to bind to its protein partner, transducin, made up of three subunits (green, yellow, and purple). The binding amplifies the visual signal, which then streams onward through the optic nerve for further processing in the brain—and the ability to avoid tripping over the dog.

Previous Page Next Page