196 Search Results for "covid-19"

U.K. Study Shows Power of Digital Contact Tracing for COVID-19

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s been much interest in using digital technology to help contain the spread of COVID-19 in our communities. The idea is to make available opt-in smart phone apps that create a log of other apps operating on the phones of nearby participants. If a participant tests positive for COVID-19 and enters the result, the app will then send automatic alerts to those phones—and participants—who recently came into close proximity with them.

In theory, digital tracing would be much faster and more efficient than the challenging detective work involved in traditional contract tracing. But many have wondered how well such an opt-in system would work in practice. A recent paper, published in the journal Nature, shows that a COVID-19 digital tracing app worked quite well in the United Kingdom [1].

The research comes from Christophe Fraser, Oxford University, and his colleagues in the U.K. The team studied the NHS COVID-19 app, the National Health Service’s digital tracing smart phone app for England and Wales. Launched in September 2020, the app has been downloaded onto 21 million devices and used regularly by about half of eligible smart phone users, ages 16 and older. That’s 16.5 million of 33.7 million people, or more than a quarter of the total population of England and Wales.

From the end of September through December 2020, the app sent about 1.7 million exposure notifications. That’s 4.4 on average for every person with COVID-19 who opted-in to the digital tracing app.

The researchers estimate that around 6 percent of app users who received notifications of close contact with a positive case went on to test positive themselves. That’s similar to what’s been observed in traditional contact tracing.

Next, they used two different approaches to construct mathematical and statistical models to determine how likely it was that a notified contact, if infected, would quarantine in a timely manner. Though the two approaches arrived at somewhat different answers, their combined outputs suggest that the app may have stopped anywhere from 200,000 to 900,000 infections in just three months. This means that roughly one case was averted for each COVID-19 case that consented to having their contacts notified through the app.

Of course, these apps are only as good as the total number of people who download and use them faithfully. They estimate that for every 1 percent increase in app users, the number of COVID-19 cases could be reduced by another 1 or 2 percent. While those numbers might sound small, they can be quite significant when one considers the devastating impact that COVID-19 continues to have on the lives and livelihoods of people all around the world.

Reference:

[1] The epidemiological impact of the NHS COVID-19 App. Wymant C, Ferretti L, Tsallis D, Charalambides M, Abeler-Dörner L, Bonsall D, Hinch R, Kendall M, Milsom L, Ayres M, Holmes C, Briers M, Fraser C. Nature. 2021 May 12.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Christophe Fraser (Oxford University, UK)

Giving Thanks to Everyone at NIH’s COVID-19 Vaccine Clinic

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

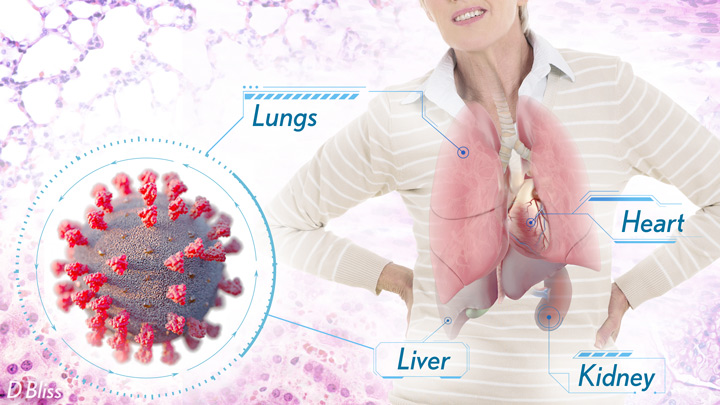

How Severe COVID-19 Can Tragically Lead to Lung Failure and Death

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

More than 3 million people around the world, now tragically including thousands every day in India, have lost their lives to severe COVID-19. Though incredible progress has been made in a little more than a year to develop effective vaccines, diagnostic tests, and treatments, there’s still much we don’t know about what precisely happens in the lungs and other parts of the body that leads to lethal outcomes.

Two recent studies in the journal Nature provide some of the most-detailed analyses yet about the effects on the human body of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 [1,2]. The research shows that in people with advanced infections, SARS-CoV-2 often unleashes a devastating series of host events in the lungs prior to death. These events include runaway inflammation and rampant tissue destruction that the lungs cannot repair.

Both studies were supported by NIH. One comes from a team led by Benjamin Izar, Columbia University, New York. The other involves a group led by Aviv Regev, now at Genentech, and formerly at Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA.

Each team analyzed samples of essential tissues gathered from COVID-19 patients shortly after their deaths. Izar’s team set up a rapid autopsy program to collect and freeze samples within hours of death. He and his team performed single-cell RNA sequencing on about 116,000 cells from the lung tissue of 19 men and women. Similarly, Regev’s team developed an autopsy biobank that included 420 total samples from 11 organ systems, which were used to generate multiple single-cell atlases of tissues from the lung, kidney, liver, and heart.

Izar’s team found that the lungs of people who died of COVID-19 were filled with immune cells called macrophages. While macrophages normally help to fight an infectious virus, they seemed in this case to produce a vicious cycle of severe inflammation that further damaged lung tissue. The researchers also discovered that the macrophages produced high levels of IL-1β, a type of small inflammatory protein called a cytokine. This suggests that drugs to reduce effects of IL-1β might have promise to control lung inflammation in the sickest patients.

As a person clears and recovers from a typical respiratory infection, such as the flu, the lung repairs the damage. But in severe COVID-19, both studies suggest this isn’t always possible. Not only does SARS-CoV-2 destroy cells within air sacs, called alveoli, that are essential for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide, but the unchecked inflammation apparently also impairs remaining cells from repairing the damage. In fact, the lungs’ regenerative cells are suspended in a kind of reparative limbo, unable to complete the last steps needed to replace healthy alveolar tissue.

In both studies, the lung tissue also contained an unusually large number of fibroblast cells. Izar’s team went a step further to show increased numbers of a specific type of pathological fibroblast, which likely drives the rapid lung scarring (pulmonary fibrosis) seen in severe COVID-19. The findings point to specific fibroblast proteins that may serve as drug targets to block deleterious effects.

Regev’s team also describes how the virus affects other parts of the body. One surprising discovery was there was scant evidence of direct SARS-CoV-2 infection in the liver, kidney, or heart tissue of the deceased. Yet, a closer look heart tissue revealed widespread damage, documenting that many different coronary cell types had altered their genetic programs. It’s still to be determined if that’s because the virus had already been cleared from the heart prior to death. Alternatively, the heart damage might not be caused directly by SARS-CoV-2, and may arise from secondary immune and/or metabolic disruptions.

Together, these two studies provide clearer pictures of the pathology in the most severe and lethal cases of COVID-19. The data from these cell atlases has been made freely available for other researchers around the world to explore and analyze. The hope is that these vast data sets, together with future analyses and studies of people who’ve tragically lost their lives to this pandemic, will improve our understanding of long-term complications in patients who’ve survived. They also will now serve as an important foundational resource for the development of promising therapies, with the goal of preventing future complications and deaths due to COVID-19.

References:

[1] A molecular single-cell lung atlas of lethal COVID-19. Melms JC, Biermann J, Huang H, Wang Y, Nair A, Tagore S, Katsyv I, Rendeiro AF, Amin AD, Schapiro D, Frangieh CJ, Luoma AM, Filliol A, Fang Y, Ravichandran H, Clausi MG, Alba GA, Rogava M, Chen SW, Ho P, Montoro DT, Kornberg AE, Han AS, Bakhoum MF, Anandasabapathy N, Suárez-Fariñas M, Bakhoum SF, Bram Y, Borczuk A, Guo XV, Lefkowitch JH, Marboe C, Lagana SM, Del Portillo A, Zorn E, Markowitz GS, Schwabe RF, Schwartz RE, Elemento O, Saqi A, Hibshoosh H, Que J, Izar B. Nature. 2021 Apr 29.

[2] COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Delorey TM, Ziegler CGK, Heimberg G, Normand R, Shalek AK, Villani AC, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Regev A. et al. Nature. 2021 Apr 29.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Izar Lab (Columbia University, New York)

Aviv Regev (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Dynamic View of Spike Protein Reveals Prime Targets for COVID-19 Treatments

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

This striking portrait features the spike protein that crowns SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. This highly flexible protein has settled here into one of its many possible conformations during the process of docking onto a human cell before infecting it.

This portrait, however, isn’t painted on canvas. It was created on a computer screen from sophisticated 3D simulations of the spike protein in action. The aim was to map its many shape-shifting maneuvers accurately at the atomic level in hopes of detecting exploitable structural vulnerabilities to thwart the virus.

For example, notice the many chain-like structures (green) that adorn the protein’s surface (white). They are sugar molecules called glycans that are thought to shield the spike protein by sweeping away antibodies. Also notice areas (purple) that the simulation identified as the most-attractive targets for antibodies, based on their apparent lack of protection by those glycans.

This work, published recently in the journal PLoS Computational Biology [1], was performed by a German research team that included Mateusz Sikora, Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Frankfurt. The researchers used a computer application called molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to power up and model the conformational changes in the spike protein on a time scale of a few microseconds. (A microsecond is 0.000001 second.)

The new simulations suggest that glycans act as a dynamic shield on the spike protein. They liken them to windshield wipers on a car. Rather than being fixed in space, those glycans sweep back and forth to protect more of the protein surface than initially meets the eye.

But just as wipers miss spots on a windshield that lie beyond their tips, glycans also miss spots of the protein just beyond their reach. It’s those spots that the researchers suggest might be prime targets on the spike protein that are especially promising for the design of future vaccines and therapeutic antibodies.

This same approach can now be applied to identifying weak spots in the coronavirus’s armor. It also may help researchers understand more fully the implications of newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. The hope is that by capturing this devastating virus and its most critical proteins in action, we can continue to develop and improve upon vaccines and therapeutics.

Reference:

[1] Computational epitope map of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Sikora M, von Bülow S, Blanc FEC, Gecht M, Covino R, Hummer G. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021 Apr 1;17(4):e1008790.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Mateusz Sikora (Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Frankfurt, Germany)

The surprising properties of the coronavirus envelope (Interview with Mateusz Sikora), Scilog, November 16, 2020.

A Real-World Look at COVID-19 Vaccines Versus New Variants

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Clinical trials have shown the COVID-19 vaccines now being administered around the country are highly effective in protecting fully vaccinated individuals from the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. But will they continue to offer sufficient protection as the frequency of more transmissible and, in some cases, deadly emerging variants rise?

More study and time is needed to fully answer this question. But new data from Israel offers an early look at how the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is holding up in the real world against coronavirus “variants of concern,” including the B.1.1.7 “U.K. variant” and the B.1.351 “South African variant.” And, while there is some evidence of breakthrough infections, the findings overall are encouraging.

Israel was an obvious place to look for answers to breakthrough infections. By last March, more than 80 percent of the country’s vaccine-eligible population had received at least one dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. An earlier study in Israel showed that the vaccine offered 94 percent to 96 percent protection against infection across age groups, comparable to the results of clinical trials. But it didn’t dig into any important differences in infection rates with newly emerging variants, post-vaccination.

To dig a little deeper into this possibility, a team led by Adi Stern, Tel Aviv University, and Shay Ben-Shachar, Clalit Research Institute, Tel Aviv, looked for evidence of breakthrough infections in several hundred people who’d had at least one dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine [1]. The idea was, if this vaccine were less effective in protecting against new variants of concern, the proportion of infections caused by them should be higher in vaccinated compared to unvaccinated individuals.

During the study, reported as a pre-print in MedRxiv, it became clear that B.1.1.7 was the predominant SARS-CoV-2 variant in Israel, with its frequency increasing over time. By comparison, the B.1.351 “South African” variant was rare, accounting for less than 1 percent of cases sampled in the study. No other variants of concern, as defined by the World Health Organization, were detected.

In total, the researchers sequenced SARS-CoV-2 from more than 800 samples, including vaccinated individuals and matched unvaccinated individuals with similar characteristics including age, sex, and geographic location. They identified nearly 250 instances in which an individual became infected with SARS-CoV-2 after receiving their first vaccine dose, meaning that they were only partially protected. Almost 150 got infected sometime after receiving the second dose.

Interestingly, the evidence showed that these breakthrough infections with the B.1.1.7 variant occurred slightly more often in people after the first vaccine dose compared to unvaccinated people. No evidence was found for increased breakthrough rates of B.1.1.7 a week or more after the second dose. In contrast, after the second vaccine dose, infection with the B.1.351 became slightly more frequent. The findings show that people remain susceptible to B.1.1.7 following a single dose of vaccine. They also suggest that the two-dose vaccine may be slightly less effective against B.1.351 compared to the original or B.1.1.7 variants.

It’s important to note, however, that the researchers only observed 11 infections with the B.1.351 variant—eight of them in individuals vaccinated with two doses. Interestingly, all eight tested positive seven to 13 days after receiving their second dose. No one in the study tested positive for this variant two weeks or more after the second dose.

Many questions remain, including whether the vaccines reduced the duration and/or severity of infections. Nevertheless, the findings are a reminder that—while these vaccines offer remarkable protection—they are not foolproof. Breakthrough infections can and do occur.

In fact, in a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine, NIH-supported researchers detailed the experiences of two fully vaccinated individuals in New York who tested positive for COVID-19 [2]. Though both recovered quickly at home, genomic data in those cases revealed multiple mutations in both viral samples, including a variant first identified in South Africa and Brazil, and another, which has been spreading in New York since November.

These findings in Israel and the United States also highlight the importance of tracking coronavirus variants and making sure that all eligible individuals get fully vaccinated as soon as they have the opportunity. They show that COVID-19 testing will continue to play an important role, even in those who’ve already been vaccinated. This is even more important now as new variants continue to rise in frequency.

Just over 100 million Americans aged 18 and older—about 40 percent of adults—are now fully vaccinated [3]. However, we need to get that number much higher. If you or a loved one haven’t yet been vaccinated, please consider doing so. It will help to save lives and bring this pandemic to an end.

References:

[1] Evidence for increased breakthrough rates of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in BNT162b2 mRNA vaccinated individuals. Kustin T et al. medRxiv. April 16, 2021.

[2] Vaccine breakthrough infections with SARS-CoV-2 variants. Hacisuleyman E, Hale C, Saito Y, Blachere NE, Bergh M, Conlon EG, Schaefer-Babajew DJ, DaSilva J, Muecksch F, Gaebler C, Lifton R, Nussenzweig MC, Hatziioannou T, Bieniasz PD, Darnell RB. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 21.

[3] COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Stern Lab (Tel Aviv University, Israel)

Ben-Shachar Lab (Clalit Research Institute, Tel Aviv, Israel)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Building Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccines

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Learning from History: Fauci Donates Model to Smithsonian’s COVID-19 Collection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Not too long after the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic reached the United States, museum curators began collecting material to document the history of this devastating public health crisis and our nation’s response to it. To help tell this story, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History recently scored a donation from my friend and colleague Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Widely recognized for serving as a clear voice for science throughout the pandemic, Fauci gave the museum his much-used model of SARS-CoV-2, which is the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. This model, which is based on work conducted by NIH-supported electron microscopists and structural biologists, was 3D printed right here at NIH. By the way, I’m lucky enough to have one too.

Both of these models have “met” an amazing array of people—from presidents to congresspeople to journalists to average citizens—as part of our efforts to help folks understand SARS-CoV-2 and the crucial role of its surface spike proteins. As shown in this brief video, Fauci raised his model one last time and then, ever the public ambassador for science, turned his virtual donation into a memorable teaching moment. I recommend you take a minute or two to watch it.

The donation took place during a virtual ceremony in which the National Museum of American History awarded Fauci its prestigious Great Americans Medal. He received the award for his lifetime contributions to the nation’s ideals and for making a lasting impact on public health via his many philanthropic and humanitarian efforts. Fauci joined an impressive list of luminaries in receiving this honor, including former Secretaries of State Madeleine Albright and General Colin Powell; journalist Tom Brokaw; baseball great Cal Ripken Jr.; tennis star Billie Jean King; and musician Paul Simon. It’s a well-deserved honor for a physician-scientist who’s advised seven presidents on a range of domestic and global health issues, from HIV/AIDS to Ebola to COVID-19.

With Fauci’s model now enshrined as an official piece of U.S. history, the Smithsonian and other museums around the world are stepping up their efforts to gather additional artifacts related to COVID-19 and to chronicle its impacts on the health and economy of our nation. Hopefully, future generations will learn from this history so that humankind is not doomed to repeat it.

It is interesting to note that the National Museum of American History’s collection contains few artifacts from another tragic chapter in our nation’s past: the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. One reason this pandemic went largely undocumented is that, like so many of their fellow citizens, curators chose to overlook its devastating impacts and instead turn toward the future.

Today, museum staffers across the country and around the world are stepping up to the challenge of documenting COVID-19’s history with great creativity, collecting all variety of masks, test kits, vaccine vials, and even a few ventilators. At the NIH’s main campus in Bethesda, MD, the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum is busy preparing a small exhibit of scientific and clinical artifacts that could open as early as the summer of 2021. The museum is also collecting oral histories as part of its “Behind the Mask” project. So far, more than 50 interviews have been conducted with NIH staff, including a scientist who’s helping the hard-hit Navajo Nation during the pandemic; a Clinical Center nurse who’s treating patients with COVID-19, and a mental health professional who’s had to change expectations since the outbreak.

The pandemic isn’t over yet. All of us need to do our part by getting vaccinated against COVID-19 and taking other precautions to prevent the virus’s deadly spread. But won’t it great when—hopefully, one day soon—we can relegate this terrible pandemic to the museums and the history books!

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Video: National Museum of American History Presents The Great Americans Medal to Anthony S. Fauci (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.)

National Museum of American History (Smithsonian)

The Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum (NIH)

Mapping Severe COVID-19 in the Lungs at Single-Cell Resolution

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A crucial question for COVID-19 researchers is what causes progression of the initial infection, leading to life-threatening respiratory illness. A good place to look for clues is in the lungs of those COVID-19 patients who’ve tragically lost their lives to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), in which fluid and cellular infiltrates build up in the lung’s air sacs, called alveoli, keeping them from exchanging oxygen with the bloodstream.

As shown above, a team of NIH-funded researchers has done just that, capturing changes in the lungs over the course of a COVID-19 infection at unprecedented, single-cell resolution. These imaging data add evidence that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, primarily infects cells at the surface of the air sacs. Their findings also offer valuable clues for treating the most severe consequences of COVID-19, suggesting that a certain type of scavenging immune cell might be driving the widespread lung inflammation that leads to ARDS.

The findings, published in Nature [1], come from Olivier Elemento and Robert E. Schwartz, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. They already knew from earlier COVID-19 studies about the body’s own immune response causing the lung inflammation that leads to ARDS. What was missing was an understanding of the precise interplay between immune cells and lung tissue infected with SARS-CoV-2. It also wasn’t clear how the ARDS seen with COVID-19 compared to the ARDS seen in other serious respiratory diseases, including influenza and bacterial pneumonia.

Traditional tissue analysis uses chemical stains or tagged antibodies to label certain proteins and visualize important features in autopsied human tissues. But using these older techniques, it isn’t possible to capture more than a few such proteins at once. To get a more finely detailed view, the researchers used a more advanced technology called imaging mass cytometry [2].

This approach uses a collection of lanthanide metal-tagged antibodies to label simultaneously dozens of molecular markers on cells within tissues. Next, a special laser scans the labeled tissue sections, which vaporizes the heavy metal tags. As the metals are vaporized, their distinct signatures are detected in a mass spectrometer along with their spatial position relative to the laser. The technique makes it possible to map precisely where a diversity of distinct cell types is located in a tissue sample with respect to one another.

In the new study, the researchers applied the method to 19 lung tissue samples from patients who had died of severe COVID-19, acute bacterial pneumonia, or bacterial or influenza-related ARDS. They included 36 markers to differentiate various types of lung and immune cells as well as the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and molecular signs of immune activation, inflammation, and cell death. For comparison, they also mapped four lung tissue samples from people who had died without lung disease.

Altogether, they captured more than 200 lung tissue maps, representing more than 660,000 cells across all the tissues sampled. Those images showed in all cases that respiratory infection led to a thickening of the walls surrounding alveoli as immune cells entered. They also showed an increase in cell death in infected compared to healthy lungs.

Their maps suggest that what happens in the lungs of COVID-19 patients who die with ARDS isn’t entirely unique. It’s similar to what happens in the lungs of those with other life-threatening respiratory infections who also die with ARDS.

They did, however, reveal a potentially prominent role in COVID-19 for white blood cells called macrophages. The results showed that macrophages are much more abundant in the lungs of severe COVID-19 patients compared to other lung infections.

In late COVID-19, macrophages also increase in the walls of alveoli, where they interact with lung cells known as fibroblasts. This suggests these interactions may play a role in the buildup of damaging fibrous tissue, or scarring, in the alveoli that tends to be seen in severe COVID-19 respiratory infections.

While the virus initiates this life-threatening damage, its progression may not depend on the persistence of the virus, but on an overreaction of the immune system. This may explain why immunomodulatory treatments like dexamethasone can provide benefit to the sickest patients with COVID-19. To learn even more, the researchers are making their data and maps available as a resource for scientists around the world who are busily working to understand this devastating illness and help put an end to the terrible toll caused by this pandemic.

References:

[1] The spatial landscape of lung pathology during COVID-19 progression. Rendeiro AF, Ravichandran H, Bram Y, Chandar V, Kim J, Meydan C, Park J, Foox J, Hether T, Warren S, Kim Y, Reeves J, Salvatore S, Mason CE, Swanson EC, Borczuk AC, Elemento O, Schwartz RE. Nature. 2021 Mar 29.

[2] Mass cytometry imaging for the study of human diseases-applications and data analysis strategies. Baharlou H, Canete NP, Cunningham AL, Harman AN, Patrick E. Front Immunol. 2019 Nov 14;10:2657.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Elemento Lab (Weill Cornell Medicine, New York)

Schwartz Lab (Weill Cornell Medicine)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Cancer Institute

New Initiative Puts At-Home Testing to Work in the Fight Against COVID-19

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thankfully COVID-19 testing is now more widely available than it was earlier in the pandemic. But getting tested often still involves going to a doctor’s office or community testing site and waiting as long as a couple of days for the results. Testing would be so much easier if people could do it themselves at home. If the result came up positive, a person could immediately self-isolate, helping to stop the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, from spreading any further in their communities.

That’s why I’m happy to report that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in close collaboration with state and local public health departments and with NIH, has begun an innovative community health initiative called “Say Yes! COVID Test.” The initiative, the first large-scale evaluation of community-wide, self-administered COVID-19 testing, was launched last week in Pitt County, NC, and will start soon in Chattanooga/Hamilton County, TN.

The initiative will provide as many as 160,000 residents in these two locales with free access to rapid COVID-19 home tests, supplied through NIH’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative. Participants can administer these easy-to-use tests themselves up to three times a week for one month. The goal is to assess the benefits of self-administered COVID-19 testing and help guide other communities in implementing similar future programs to slow the spread of COVID-19.

The counties in North Carolina and Tennessee were selected based on several criteria. These included local infection rates; public availability of accurate COVID-19 tracking data, such as that gathered by wastewater surveillance; the presence of local infrastructure needed to support the project; and existing community relationships through RADx’s Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) program. Taken together, these criteria also help to ensure that vulnerable and underserved populations will benefit from the initiative.

The test is called the QuickVue At-Home COVID-19 Test. Developed with RADx support by San Diego-based diagnostic company Quidel, this test is easily performed with a nasal swab and offers results in just 10 minutes. Last week, the test was among several authorized by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for over-the-counter use to screen for COVID-19 at home.

Participants can order their QuickVue test kits online for home delivery or local pick up. A free online tool, which was developed with NIH support by CareEvolution, LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, will also be available to provide testing instructions, help in understanding test results, and text message reminders about testing. This innovative tool is also available as a smartphone app.

A recent study, supported by the RADx initiative, found that rapid antigen testing for COVID-19, when conducted at least three times per week, achieves a viral detection level on par with the gold standard of PCR-based COVID-19 testing processed in a lab [1]. That’s especially significant considering the other advantages of a low-cost, self-administered rapid test, including confidential results at home in minutes.

The Say Yes! COVID Test initiative is an important next step in informing the best testing strategies in communities all over the country to end this and future pandemics. The initiative will also help to determine how readily people accept such testing when it’s made available to them. If the foundational data looks promising, the hope is that rapid at-home tests will help to encourage people to protect themselves and others by following the three W’s (Wear a mask. Wash your hands. Watch your distance), getting vaccinated, and saying “Yes” to the COVID-19 test.

Reference:

[1] Longitudinal assessment of diagnostic test performance over the course of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Smith RL, Gibson LL, Martinez PP, Heetderks WJ, McManus DD, Brooke CB, et al. medRxiv, 2021 March 20.

Links:

CDC and NIH bring COVID-19 self-testing to residents in two locales, NIH News Release, March 31, 2021

Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) (NIH)

COVID-19 Testing (CDC)

Quidel Corporation (San Diego, CA)

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Continues to Advance Over-the Counter and Other Screening Test Development, FDA News Release, March 31, 2021

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Previous Page Next Page