Study Reveals How Epstein-Barr Virus May Lead to Cancer

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Chances are good that you’ve had an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, usually during childhood. More than 90 percent of us have, though we often don’t know it. That’s because most EBV infections are mild or produce no symptoms at all.

But in some people, EBV can lead to other health problems. The virus can cause infectious mononucleosis (“mono”), type 1 diabetes, and other ailments. It also can persist in our bodies for years and cause increased risk later in life for certain cancers, such as lymphoma, leukemia, and head and neck cancer. Now, an NIH-funded team has some of the best evidence yet to explain how this EBV that hangs around may lead to cancer [1].

The paper, published recently in the journal Nature, shows that a key viral protein readily binds to a particular spot on a particular human chromosome. Where the protein accumulates, the chromosome becomes more prone to breaking for reasons that aren’t yet fully known. What the study makes clearer is that the breakage produces latently infected cells that are more likely over time to become cancerous.

This discovery paves the way potentially for ways to screen for and identify those at particular risk for developing EBV-associated cancers. It may also fuel the development of promising new ways to prevent these cancers from arising in the first place.

The work comes from a team led by Don Cleveland and Julia Su Zhou Li, University of California San Diego’s Ludwig Cancer Research, La Jolla, CA. Over the years, it’s been established that EBV, a type of herpes virus, often is detected in certain cancers, particularly in people with a long-term latent infection. What interested the team is a viral protein, called EBNA1, which routinely turns up in those same EBV-related cancers.

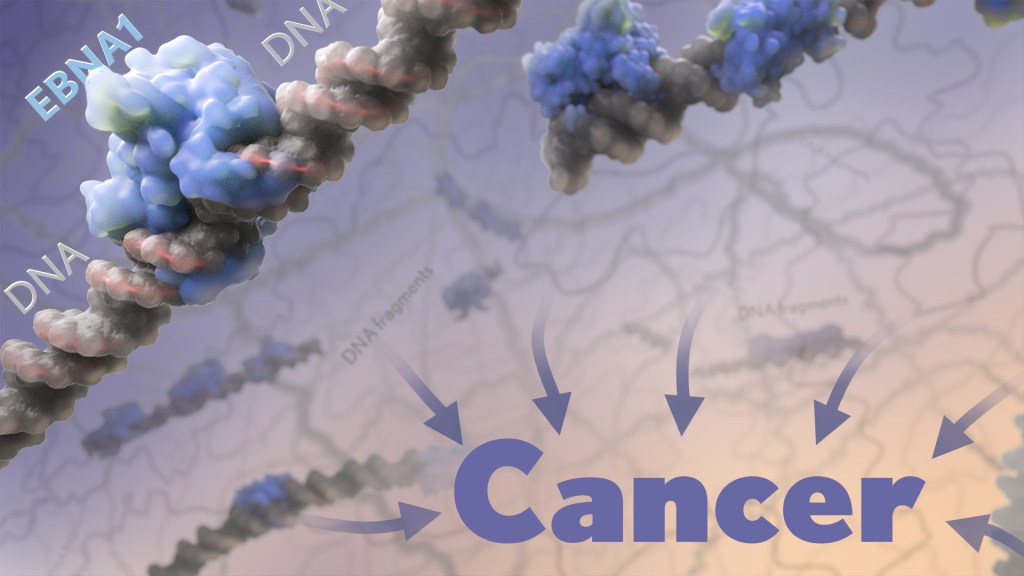

The EBNA1 protein is especially interesting because it binds viral DNA in particular spots, which allows the virus to persist and make more copies of itself. This discovery raised the intriguing possibility that the protein may also bind similar sequences in human DNA. While it had been suggested previously that this interaction might play a role in EBV-associated cancers, the details had remained murky—until now.

In the new study, the researchers first made uninfected human cells produce the viral EBNA1 protein. They then peered inside them with a microscope to see where those proteins went. In both healthy and cancerous human cells, they watched as EBNA1 proteins built up at two distinct spots and confirmed that this accumulation was dependent on the protein’s ability to bind DNA.

Next, they mapped where exactly EBNA1 binds to human DNA. Interestingly, it was along a repetitive non-protein-coding stretch of DNA on human chromosome 11. This region includes more than 300 copies of an 18-letter sequence that looks quite similar to the EBNA1-binding sites in its own viral genome.

What’s more, the researchers noticed that the repetitive DNA there takes on a structure that’s known for being unstable. And these so-called fragile sites are inherently prone to breaking.

The team went on to uncover evidence that the buildup of EBNA1 at this already fragile site only makes matters worse. In EBV-infected cells, increasing the amount of EBNA1 protein led to more chromosome 11 breaks. Those breaks showed up within a single day in about 40 percent of cells.

For these cells, those breaks also may be a double whammy. That’s because the breaks are located next to neighboring genes with long recognized roles in regulating cell growth. When altered, these genes can contribute to turning a cell cancerous.

To further nail down the link to cancer, the researchers looked to whole-genome sequencing data for more than 2,400 cancers including 38 tumor types from the international Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes consortium [2]. They found that tumors with detectable EBV also had an unusually high number of chromosome 11 abnormalities. In fact, that was true in every single case of head and neck cancer.

The findings suggest that people will vary in their susceptibility to EBNA1-induced DNA breaks along chromosome 11 based on the amount of EBNA1 protein in their latently infected cells. It also will depend on the number of EBV-like DNA repeats present in their DNA.

Given these new findings, it’s worth noting that the presence of EBV and the very same viral protein has been implicated also in the link between EBV and multiple sclerosis (MS) [3]. Together, these recent findings are a reminder of the value in pursuing an EBV vaccine that might thwart this infection and its associated conditions, including certain cancers and MS. And, we’re getting there. In fact, an early-stage clinical trial for an experimental EBV vaccine is now ongoing here at the NIH Clinical Center.

References:

[1] Chromosomal fragile site breakage by EBV-encoded EBNA1 at clustered repeats. Li JSZ, Abbasi A, Kim DH, Lippman SM, Alexandrov LB, Cleveland DW. Nature. 2023 Apr 12.

[2] Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium. Nature.2020 Feb;578(7793):82-93.

[3] Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Lanz TV, Brewer RC, Steinman L, Robinson WH, et al. Nature. 2022 Mar;603(7900):321-327.

Links:

About Epstein-Barr Virus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta)

Head and Neck Cancer (National Cancer Institute,/NIH)

Multiple Sclerosis (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Don W. Cleveland Lab (University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; National Cancer Institute

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Excelente publicacion

Can Covid reactivate Ebstein Barr or other latent viruses while you are sick or be part of “Long Covid”?

Is there any research to see or watch for increasing or reoccurrence of these infections or cancers due to them post Covid?

Very interesting article. I’m glad progress is being made in this area.

I wonder if any checking has been done in ME/CFS and, as another commenter asked, other infection associated conditions such as Long Covid?

There’s been a query about whether EBV could contribute to onset of ME/CFS in some patients, but not, as far as I know, with such advanced techniques.

Myself, my immune system has no memory of me ever having had EBV, but it knows I’ve had HHV-1 and Lyme disease (my ME/CFS onset was before the tick bite when I got Lyme: onset of ME/CFS was when I had the flu in a campus outbreak). As ME/CFS onset is documented following various infections from EBV to Q fever to Giardia to enterovirus to more than one coronavirus, and suspected to be associated with fungal infections as well, it seems less specific than this EBNA1 protein. But maybe there could be some sort of conserved sequence in these microbes, with a similar effect to the EBV sequence discussed?

Best,

WillowJ

I could believe it. Scary times that’s for sure.

Buenos días son temas interesantes los planteados en esta página un reconocimiento muy sincero y sigan adelante