How Immunity Generated from COVID-19 Vaccines Differs from an Infection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A key issue as we move closer to ending the pandemic is determining more precisely how long people exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 virus, will make neutralizing antibodies against this dangerous coronavirus. Finding the answer is also potentially complicated with new SARS-CoV-2 “variants of concern” appearing around the world that could find ways to evade acquired immunity, increasing the chances of new outbreaks.

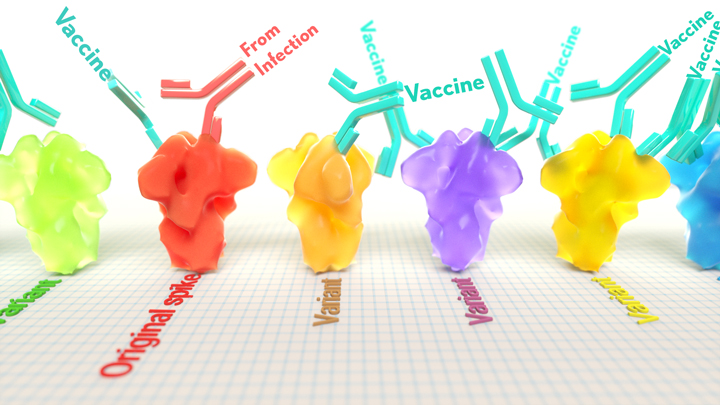

Now, a new NIH-supported study shows that the answer to this question will vary based on how an individual’s antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were generated: over the course of a naturally acquired infection or from a COVID-19 vaccine. The new evidence shows that protective antibodies generated in response to an mRNA vaccine will target a broader range of SARS-CoV-2 variants carrying “single letter” changes in a key portion of their spike protein compared to antibodies acquired from an infection.

These results add to evidence that people with acquired immunity may have differing levels of protection to emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. More importantly, the data provide further documentation that those who’ve had and recovered from a COVID-19 infection still stand to benefit from getting vaccinated.

These latest findings come from Jesse Bloom, Allison Greaney, and their team at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. In an earlier study, this same team focused on the receptor binding domain (RBD), a key region of the spike protein that studs SARS-CoV-2’s outer surface. This RBD is especially important because the virus uses this part of its spike protein to anchor to another protein called ACE2 on human cells before infecting them. That makes RBD a prime target for both naturally acquired antibodies and those generated by vaccines. Using a method called deep mutational scanning, the Seattle group’s previous study mapped out all possible mutations in the RBD that would change the ability of the virus to bind ACE2 and/or for RBD-directed antibodies to strike their targets.

In their new study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Bloom, Greaney, and colleagues looked again to the thousands of possible RBD variants to understand how antibodies might be expected to hit their targets there [1]. This time, they wanted to explore any differences between RBD-directed antibodies based on how they were acquired.

Again, they turned to deep mutational scanning. First, they created libraries of all 3,800 possible RBD single amino acid mutants and exposed the libraries to samples taken from vaccinated individuals and unvaccinated individuals who’d been previously infected. All vaccinated individuals had received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine. This vaccine works by prompting a person’s cells to produce the spike protein, thereby launching an immune response and the production of antibodies.

By closely examining the results, the researchers uncovered important differences between acquired immunity in people who’d been vaccinated and unvaccinated people who’d been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, antibodies elicited by the mRNA vaccine were more focused to the RBD compared to antibodies elicited by an infection, which more often targeted other portions of the spike protein. Importantly, the vaccine-elicited antibodies targeted a broader range of places on the RBD than those elicited by natural infection.

These findings suggest that natural immunity and vaccine-generated immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will differ in how they recognize new viral variants. What’s more, antibodies acquired with the help of a vaccine may be more likely to target new SARS-CoV-2 variants potently, even when the variants carry new mutations in the RBD.

It’s not entirely clear why these differences in vaccine- and infection-elicited antibody responses exist. In both cases, RBD-directed antibodies are acquired from the immune system’s recognition and response to viral spike proteins. The Seattle team suggests these differences may arise because the vaccine presents the viral protein in slightly different conformations.

Also, it’s possible that mRNA delivery may change the way antigens are presented to the immune system, leading to differences in the antibodies that get produced. A third difference is that natural infection only exposes the body to the virus in the respiratory tract (unless the illness is very severe), while the vaccine is delivered to muscle, where the immune system may have an even better chance of seeing it and responding vigorously.

Whatever the underlying reasons turn out to be, it’s important to consider that humans are routinely infected and re-infected with other common coronaviruses, which are responsible for the common cold. It’s not at all unusual to catch a cold from seasonal coronaviruses year after year. That’s at least in part because those viruses tend to evolve to escape acquired immunity, much as SARS-CoV-2 is now in the process of doing.

The good news so far is that, unlike the situation for the common cold, we have now developed multiple COVID-19 vaccines. The evidence continues to suggest that acquired immunity from vaccines still offers substantial protection against the new variants now circulating around the globe.

The hope is that acquired immunity from the vaccines will indeed produce long-lasting protection against SARS-CoV-2 and bring an end to the pandemic. These new findings point encouragingly in that direction. They also serve as an important reminder to roll up your sleeve for the vaccine if you haven’t already done so, whether or not you’ve had COVID-19. Our best hope of winning this contest with the virus is to get as many people immunized now as possible. That will save lives, and reduce the likelihood of even more variants appearing that might evade protection from the current vaccines.

Reference:

[1] Antibodies elicited by mRNA-1273 vaccination bind more broadly to the receptor binding domain than do those from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Greaney AJ, Loes AN, Gentles LE, Crawford KHD, Starr TN, Malone KD, Chu HY, Bloom JD. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Jun 8.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Bloom Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Dave, no one is advocating for people to go out and get infected to get natural immunity. We’re talking about those who have already acquired that natural immunity from infection. We want that immunity acknowledged and respected rather than continuing to be harassed and ostracized and forced to get shots we don’t need.

Heather, how does one ascertain who has immunity among those previously infected? Yes, we can show the presence (and, to some extent, the amount) of antibodies, but antibodies against which epitopes are protective at what levels? Is a certain amount of a specific antibody against a specific epitope sufficient? If so, at what titer? Are multiple antibodies against multiple epitopes at low titers better than a few antibodies against a few epitopes at high titers?

What about cell-mediated immunity? Which T cells are known to provide protection against reinfection? Cytotoxic, helper, regulatory, or memory T cells? How many of which?

And how do the humoral and cellular immunities interact? If one is weak but the other is robust, is that sufficient?

If one was somehow able to determine that they had robust infection-derived immunity from the original strain (or from Alpha, or from Delta), what does that tell you about their infection-derived immunity to an infection by the Omicron variant?

As far as I know, at this time no one knows how to ascertain who has adequate immunity against reinfection from any variant of SARS-CoV-2 because no one knows what parameters need to be met to be confident of a certain level of protection.

Just my personal observation: I am over 65, had covid in Sept of 2020. I have tested for antibodies every three months and as of January 2022 I still have antibodies. I have been significantly exposed multiple times by family members (because we have all agreed to just live life) over the last year (plus), and I have been tested for Covid-19 multiple times without contracting covid again. I have not been vaccinaded. This is just my story, I am not anti vax, and I support everyones personal decision. My point is this is a personal choce we should all be free to make.

Ken – My husband and I had COVID last February 2021 and, same as you, have had our antibodies tested regularly and still have plenty. We also have been around numerous people who have tested positive for the virus (most had received their shots), go out very often to restaurants, bars, gyms, concerts, travel, etc. – and have not had so much as a sniffle since last year. We also have not been vaccinated and don’t feel the need to do it as we already have protection. And I wholeheartedly agree with you that it’s a personal choice we should all be free to make!!

A lot of truths regarding this pandemic are starting to come out. Many truths that will expose many untruths. There appears there will be a reckoning for those who have not been acting in the best interest of the public. Stay tuned. This is far from over.

The results of a study out of Qatar published in the New England Journal of Medicine on February 9, 2022 (“Protection against the Omicron Variant from Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection”) examined the protective effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection-derived immunity against symptomatic reinfection by alpha, beta, delta and omicron variants. The reinfections occurred at a median of about 9 months after the initial infections.

They found that the protective effect of previous infections ranged from about 86% to 92% for the pre-omicron variants, but only about 56% for protection against an infection by the omicron variant. Fortunately, the protection against severe to fatal disease was pretty good, about 88% for an omicron infection. That protection against severe to fatal disease also is about par for 3 doses of the mRNA vaccines.

Those results probably are a bit better than one would be expected to see in some other countries, as the median age of the Qatari population is 32.3. In the USA, for example, the median age is 38.5. The median age of the world (as of 2020) is 31.

How does anyone believe any of this after it is admitted that no virus “isolates” (isolated viruses) exist….anywhere?

Or how does anyone fall for this when RNA virus mutations occur in hours, yet the coronavirus patiently waited to mutate for 12 months, and a vaccine before it’s first variant mutation arrived in the media? No pathology was ever proved with spanish infkuenza. No pathology was ever proved with covid.The only consistent things that occured during both “pandemics” was that the media declared all as proved fact both times, with zero actual proof.And both times. Just like wars are manufactured based on propaganda so are pandemics.

Who “…admitted that no virus ‘isolates’ (isolated viruses) exist….anywhere?” and when? This would be news to me.