Crowdsourcing 600 Years of Human History

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

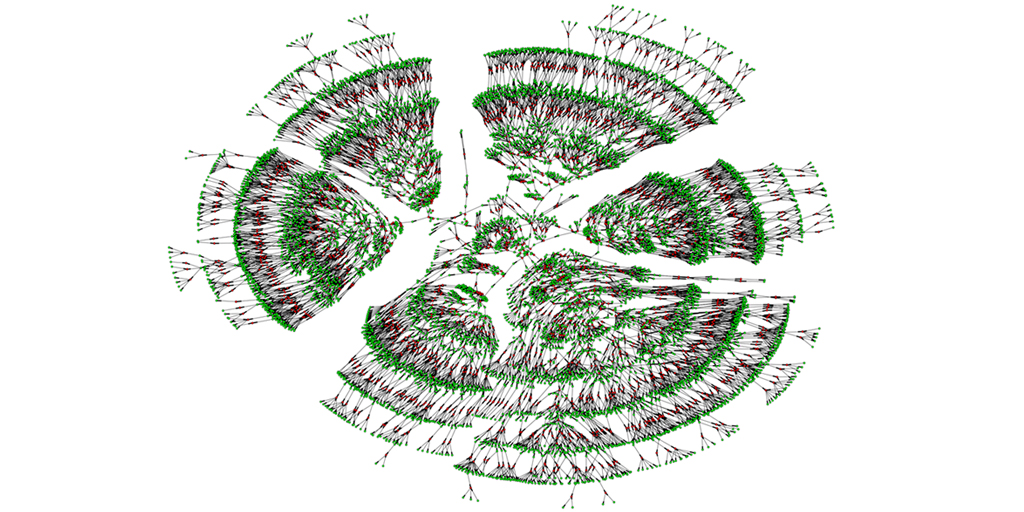

Caption: A 6,000-person family tree, showing individuals spanning seven generations (green) and their marital links (red).

Credit: Columbia University, New York City

You may have worked on constructing your family tree, perhaps listing your ancestry back to your great-grandparents. Or with so many public records now available online, you may have even uncovered enough information to discover some unexpected long-lost relatives. Or maybe you’ve even submitted a DNA sample to one of the commercial sources to see what you could learn about your ancestry. But just how big can a family tree grow using today’s genealogical tools?

A recent paper offers a truly eye-opening answer. With permission to download the publicly available, online profiles of 86 million genealogy hobbyists, most of European descent, the researchers assembled more than 5 million family trees. The largest totaled more than 13 million people! By merging each tree from the crowd-sourced and public data, including the relatively modest 6,000-person seedling shown above, the researchers were able to go back 11 generations on average to the 15th century and the days of Christopher Columbus. Doubly exciting, these large datasets offer a powerful new resource to study human health, having already provided some novel insights into our family structures, genes, and longevity.

Yaniv Erlich at Columbia University, New York City, and MyHeritage, Or Yehuda, Israel, got the idea to build a massive family tree several years ago after receiving an email from his third cousin. His cousin told him about a social genealogy site that he’d been using called Geni.com. With one side of his family already entered, Erlich decided to create his own profile to include his wife and her family members.

He noticed that the website had an interesting feature: users could merge profiles when a common relative or ancestor was found. Erlich, a computational geneticist, remembers thinking that someone like him should download the publicly available profiles in Geni.com and do something more with them.

Now, as reported in the journal Science, Erlich’s team, which received some NIH funding, has done exactly that. While the data were already available, it still wasn’t easy to do the merge. For one thing, simply downloading the 86 million profiles included in the new study from Geni.com took months. It also resulted in millions of small computer files that somehow had to be managed into a workable format.

The next step was to assemble the data into larger family trees. In the first pass, a small fraction of the profiles didn’t make sense. In some cases, the data suggested an individual had three parents. The researchers resolved those glitches and pruned out invalid branches. In the end, they generated 5.3 million family trees.

To further explore the data, Erlich and colleagues focused on profiles that included exact birth and death dates. They could see well-known historical events reflected in the data. For instance, deaths increased among young men of military age during the American Civil War, World War I, and World War II. It also showed fewer childhood deaths beginning in the 20th century, as public health measures—including improved sanitation, antibiotics, and vaccination programs—got infectious diseases under better control.

Most people in the database—85 percent—lived in Europe, the United States, or Canada. Erlich’s team used their geographic locations, past and present, to trace known migration events from the year 1400 to 1900. The data reflect Columbus’ landing in the Americas, the arrival of the first settlers aboard the Mayflower, and later the westward migration along the Oregon Trail.

The researchers also explored marriage trends over the centuries. The data show that prior to the Second Industrial Revolution in the mid-to-late 1800s, most marriages occurred between people born just 10 kilometers (6 miles) apart. Between 1650 and 1850, most people also found a spouse who was, on average, a fourth cousin.

By the end of the Second Industrial Revolution in the early 1900s, people began moving farther from home. The average distance that people now traveled to find a spouse jumped to about 100 kilometers (62 miles). However, while people were traveling farther, they continued to marry their distant cousins for another 50-plus years. The finding suggests shifting social and cultural norms, not just better transportation and more travel opportunities, drove the change.

The researchers realized they could use these large families to explore how much one’s life span is determined by genes. Their analysis suggests that environmental factors are much more important in determining how long we’ll live than our genes, with just 16 percent of longevity attributed to genetic factors. That’s at the low end of previous estimates, suggesting that a person’s circumstances and life choices are much more important in determining how long one lives than genes.

Erlich is now the chief scientific officer of MyHeritage, the parent company of Geni.com. He says the company is enriching this effort by collecting genetic and health information that can be overlaid onto the family trees. So far, they’ve gathered genomic data representing more than 1 million people. Erlich also has a separate online crowdsourcing venture based at Columbia University called DNA.Land, which allows people to upload and share their own DNA data [2]. DNA.Land has collected data for almost 90,000 people and counting.

As the NIH’s All of Us Research Program embarks soon on an effort to gather data from 1 million or more people living in the United States to accelerate research and improve health, this study is a reminder of the power of repurposing publicly available “Big Data,” gathered and shared by engaged citizen scientists, for making discoveries in ways that would have been unthinkable even just a few years ago. I, for one, can’t wait to see where it leads.

References:

[1] Quantitative analysis of population-scale family trees with millions of relatives. Kaplanis J, Gordon A, Shor T, Weissbrod O, Geiger D, Wahl M, Gershovits M, Markus B, Sheikh M, Gymrek M, Bhatia G, MacArthur DG, Price AL, Erlich Y. Science. 2018 Mar 1.

[2] DNA.Land is a framework to collect genomes and phenomes in the era of abundant genetic information. Yuan J, Gordon A, Speyer D, Aufrichtig R, Zielinski D, Pickrell J, Erlich Y. Nat Genet. 2018 Feb;50(2):160-165.

Links:

All of Us Research Program (NIH)

Erlich Lab (Columbia University, New York City)

DNA.Land (Columbia University)

My Family Health Portrait (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

NIH Support: National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Mental Health

Interesting to go through crowdsourcing. Any study on Indian Americans? Can any individual find his genealogy from this study if he is ready to participate?

thanks for your info

I am disappointed and find it disrespectful to see that Christopher Columbus is an NIH tag.