Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancers: Moving Toward More Precise Prevention

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

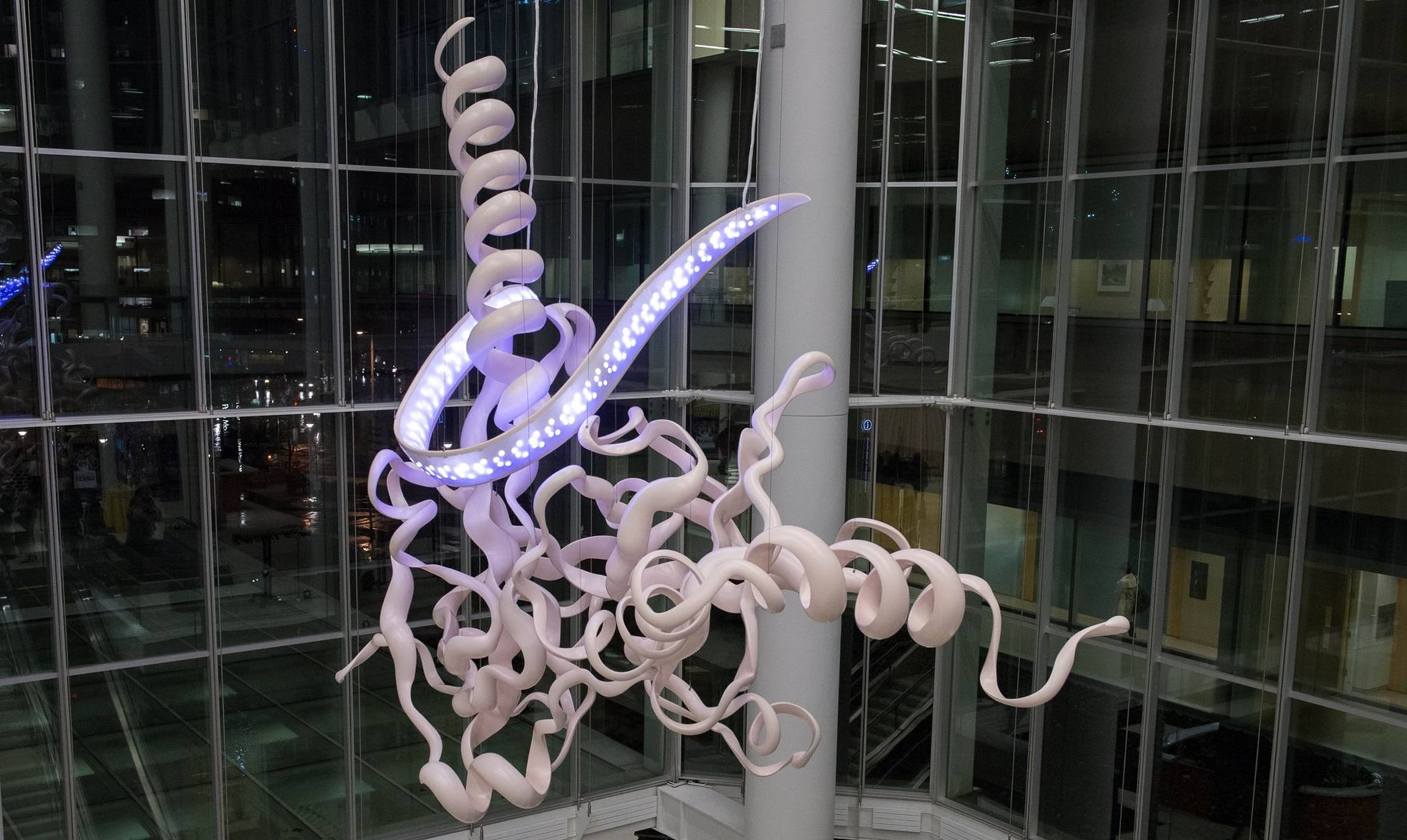

Caption: “Homologous Hope” sculpture at University of Pennsylvania depicting the part of the BRCA2 gene involved in DNA repair.

Credit: Dan Burke Photography/Penn Medicine

Inherited mutations in the BRCA1 gene and closely related BRCA2 gene account for about 5 to 10 percent of all breast cancers and 15 percent of ovarian cancers [1]. For any given individual, the likelihood that one of these mutations is responsible goes up significantly in the presence of a strong family history of developing such cancers at a relatively early age. Recently, actress Angelina Jolie revealed that she’d had her ovaries removed to reduce her risk of ovarian cancer—news that follows her courageous disclosure a couple of years ago that she’d undergone a prophylactic double mastectomy after learning she’d inherited a mutated version of BRCA1.

As life-saving as genetic testing and preventive surgery may be for certain individuals, it remains unclear exactly which women with BRCA1/2 mutations stand to benefit from these drastic measures. For example, it’s been estimated that about 65 percent of women born with a BRCA1 mutation will develop invasive breast cancer over the course of their lives—which means approximately 35 percent will not. How can women in this situation be provided with more precise, individualized guidance on cancer prevention? An international team, led by NIH-funded researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, recently took an important first step towards answering that complex question.

In a study published in the journal JAMA, the researchers analyzed genetic data and health information from more than 31,000 women with mutations in BRCA1/2. They found that among such women, the answer to whether a particular individual will develop breast cancer, ovarian cancer, both types of cancer, or neither cancer appears to vary considerably depending upon two factors: the precise type of mutation inherited and the locations of these mutations in the DNA sequences of the genes [2].

We’ve known about the roles of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in inherited breast and ovarian cancer for some time. The tumor suppressor genes, which code for proteins involved in DNA repair, were first isolated 20 years ago. However, over the years, we’ve also learned that each of these genes can contain different types of inherited mutations that vary among the individuals/families being studied. Until we understand with far greater precision how each of these many mutations (or even groups of mutations) affects individual cancer susceptibility, the best that health-care professionals can do is to offer BRCA1/2 carriers prevention guidance based on general risk calculations.

The new work by Penn’s Timothy Rebbeck, Katherine Nathanson, and their colleagues represents a significant step toward more precise and individualized risk calculations. In their study, the researchers teamed up with the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA (CIMBA), a collaboration that spans 33 nations on six continents. CIMBA’s database contains vast troves of genetic and health data on BRCA1/2 carriers from a wide range of races and ethnicities.

Of 19,591 women in the CIMBA database with BRCA1 mutations, 46 percent were diagnosed with breast cancer, 12 percent with ovarian cancer, and 5 percent with both cancers by the age of 70. It’s important to note that 37 percent of women with BRCA1 mutations had not developed cancer by the age of 70. The picture was similar for the 11,900 women with BRCA2 mutations: 52 percent were diagnosed with breast cancer, 6 percent with ovarian cancer, and 2 percent with both cancers by the age of 70. About 40 percent had not developed cancer by the age of 70.

To gather information that may help to refine the timing of prevention strategies, the Penn team also looked closely the age at which BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers were diagnosed with cancer. For BRCA1, the average age at diagnosis for breast cancer was 39.9 and 50 for ovarian cancer, while for BRCA2, the average age for breast cancer diagnosis was 42.8 and 54.5 for ovarian cancer.

Then, the researchers went on to identify BRCA1/2 mutations associated with significantly different risks of breast and ovarian cancer. For example, mutations located near the ends of BRCA1 were associated with a greater risk for breast cancer, while mutations located near the middle—specifically, in a long protein-coding sequence called exon 11—appeared to confer a higher risk of ovarian cancer. Interestingly, mutations located in or near BRCA1’s exon 11 also tended to be associated with earlier onset of both types of cancer than mutations elsewhere in the gene.

While the new findings represents encouraging progress towards more precise prevention of cancer among BRCA1/2 carriers, researchers caution that much follow-up work is needed before such information can be used to guide the very difficult decisions currently faced by such women. Ultimately, our hope is not only to spare women with BRCA1/2 who are at low risk of cancer from needless surgery, but to use this newfound knowledge to develop drugs and other less-invasive strategies for cancer prevention in high-risk women.

Developing more individualized ways to prevent inherited cancer is just one of many things we at NIH are doing to realize the full promise of precision medicine. Check out the Precision Medicine Initiative to learn more about the research needed to move such innovation into virtually all areas of health and disease.

Reference:

[1] BRCA1 and BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

[2] Association of type and location of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Rebbeck TR, Mitra N, Wan F, Sinilnikova OM, Healey S, McGuffog L, Mazoyer S, Chenevix Trench G, Easton DF, Antoniou AC, Nathanson KL, CIMBA Consortium. JAMA 2015;313(13):1347-1361.

Links:

Basser Research Center for BRCA, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Decision Tool for Women with BRCA Mutations, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA

Timothy Rebbeck, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Katherine Nathanson, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

The Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2, University of Cambridge, England

Precision Medicine Initiative (NIH)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

This study was done with 31,000 records. Myriad Genetics is holding hostage millions of records that it refuses to share that could very rapidly speed up this important work. Can you not do anything to require (or at least encourage) them to share the data?

This is a huge step forward and it’s very exciting.

Rather than the one-size-fits all risk numbers that BRCA mutation carriers currently receive in clinical reports, patients in our community want and need to see the data specific to our BRCA mutations. This helps us to make better and more informed decisions. Finding better methods to share this information is definitely necessary to realize the promise of precision medicine.

My question is: How will the PMI Network build a data commons for BRCA and other rare mutations in a way that improves decision-making for patient communities?

Thank you Dr. Collins,

As a high-risk woman, I completely agree with your comment that we need “to use this newfound knowledge to develop drugs and other less-invasive strategies for cancer prevention in high-risk women.” Please support research to fulfill the promise of drugs and other less-invasive strategies.

Looking forward to the full rollout of DataScience to advance the precision medicine cause.

It is wondrous what researchers can find with access to all that data. With open access to data that was freely given by patients to genetic testing companies, what other findings await discovery? Certainly, the willingness, curiosity, and desire are there among researchers, but the availability of the raw data isn’t.

The low hanging fruit is still yet to be plucked by cancer researchers. Please let them have access to the orchard!

It is exciting that there is finally some progress in understanding the widely varying risks conferred by specific BRCA1 and 2 mutations. That, along with the development of better alternatives to our currently barbaric options for reducing our risks and better treatments once we end up with cancer (as most of us are likely to do) will make the experience of being a woman with a BRCA1 or 2 mutation much less daunting.

I echo the sentiments of previous commenters that while the 31,000 in this study is a far better sample size than most and its analysis yielded interesting and important results (many of which, however, like the absolute risks associated with varying mutations, have not been made public), Myriad has many times that many records, data that in fact should belong to and, ultimately, benefit the patients who provided them. We must build a data commons to which patients, researchers and physicians all have access — and soon.

On another note, I would like to strongly encourage the NIH to ensure that there is adequate patient representation on the Precision Medicine Committee which there currently does not appear to be. No matter how accomplished or thoughtful a given academic or physician may be, there are important perspectives on the opportunities and challenges presented by precision medicine that will, and indeed, only can be brought to the table by people who have personally experienced and attempted to navigate hereditary illness or the threat of it.

Thank you for posting this blog! I have been trying to access the full report, but have not had any success so far. This was concise, but informative and the portion about exon 11 are especially of interest to me because my mother’s mutation is on 11 and mine is on 9. In the past I’ve tried to learn what impact location has on our risks and I’m glad to now have the information.

Is there somewhere that I can access the full research article without having to purchase it?

As a BRCA2 breast cancer survivor, I am hugely encouraged we are moving toward more precise prevention of HBOC. My family participated in an NIH study that began in the late 70s to identify a potential hereditary link to the staggering number of breast and ovarian cancer cases on my maternal side. In 2001, after more than two decades of research, a BRCA2 mutation was identified. Forever grateful to NIH. I have, however, wondered how much quicker the mutation may have been discovered if NIH collaborated with other institutions doing similar research in a race to identify the BRCA2 gene. The same goes for today. It is imperative that genetic data sharing of BRCA mutations takes place so this research can be expedited for the benefit of all. It was gut-wrenching to standby and watch my 26-year-old daughter have a prophylactic bilateral mastectomy to reduce her risk of breast cancer. We need better options. Time for Myriad to free our data.

Your research is indeed very encouraging to my family who is carrying BRCA1 del 185. Three generations in a row, the first died, the second survived cancer (ovarian and breast) and the third is contemplating whether or not to take preventive steps. I could not find in the various links info re the above mutation and would appreciate knowing if there is any study on this specific one. As an alumnus of Penn, I am really proud of the important research done in my Alma Matter.

My wife has been detected with breast cancer. I hope she will recover from it. I feel so helpless in spite of being a doctor myself. It’s nice to know that fellow doctors are trying their best to prevent it from happening.