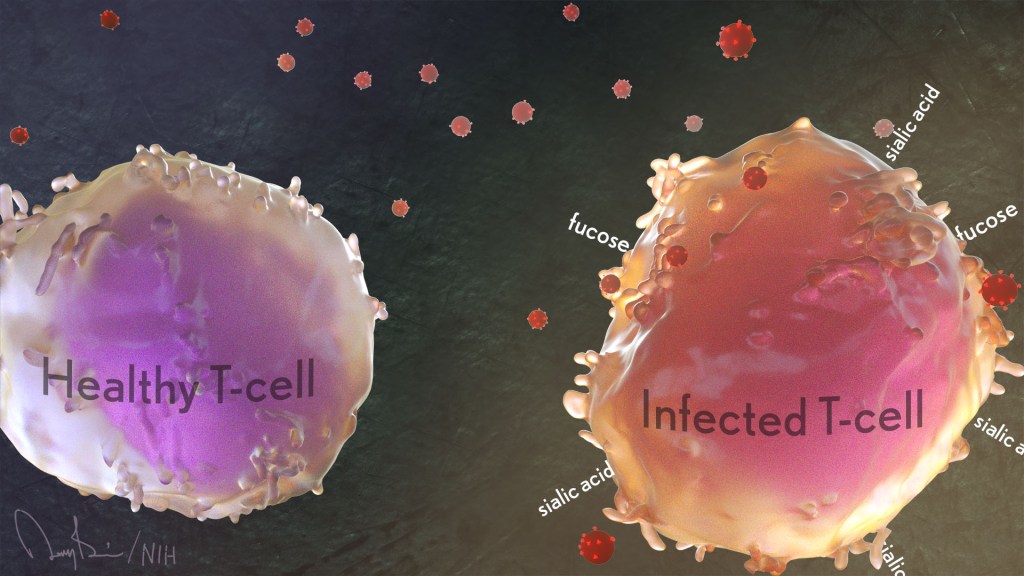

T cells

Immune Resilience is Key to a Long and Healthy Life

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Do you feel as if you or perhaps your family members are constantly coming down with illnesses that drag on longer than they should? Or, maybe you’re one of those lucky people who rarely becomes ill and, if you do, recovers faster than others.

It’s clear that some people generally are more susceptible to infectious illnesses, while others manage to stay healthier or bounce back more quickly, sometimes even into old age. Why is this? A new study from an NIH-supported team has an intriguing answer [1]. The difference, they suggest, may be explained in part by a new measure of immunity they call immune resilience—the ability of the immune system to rapidly launch attacks that defend effectively against infectious invaders and respond appropriately to other types of inflammatory stressors, including aging or other health conditions, and then quickly recover, while keeping potentially damaging inflammation under wraps.

The findings in the journal Nature Communications come from an international team led by Sunil Ahuja, University of Texas Health Science Center and the Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Personalized Medicine, both in San Antonio. To understand the role of immune resilience and its effect on longevity and health outcomes, the researchers looked at multiple other studies including healthy individuals and those with a range of health conditions that challenged their immune systems.

By looking at multiple studies in varied infectious and other contexts, they hoped to find clues as to why some people remain healthier even in the face of varied inflammatory stressors, ranging from mild to more severe. But to understand how immune resilience influences health outcomes, they first needed a way to measure or grade this immune attribute.

The researchers developed two methods for measuring immune resilience. The first metric, a laboratory test called immune health grades (IHGs), is a four-tier grading system that calculates the balance between infection-fighting CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells. IHG-I denotes the best balance tracking the highest level of resilience, and IHG-IV denotes the worst balance tracking the lowest level of immune resilience. An imbalance between the levels of these T cell types is observed in many people as they age, when they get sick, and in people with autoimmune diseases and other conditions.

The researchers also developed a second metric that looks for two patterns of expression of a select set of genes. One pattern associated with survival and the other with death. The survival-associated pattern is primarily related to immune competence, or the immune system’s ability to function swiftly and restore activities that encourage disease resistance. The mortality-associated genes are closely related to inflammation, a process through which the immune system eliminates pathogens and begins the healing process but that also underlies many disease states.

Their studies have shown that high expression of the survival-associated genes and lower expression of mortality-associated genes indicate optimal immune resilience, correlating with a longer lifespan. The opposite pattern indicates poor resilience and a greater risk of premature death. When both sets of genes are either low or high at the same time, immune resilience and mortality risks are more moderate.

In the newly reported study initiated in 2014, Ahuja and his colleagues set out to assess immune resilience in a collection of about 48,500 people, with or without various acute, repetitive, or chronic challenges to their immune systems. In an earlier study, the researchers showed that this novel way to measure immune status and resilience predicted hospitalization and mortality during acute COVID-19 across a wide age spectrum [2].

The investigators have analyzed stored blood samples and publicly available data representing people, many of whom were healthy volunteers, who had enrolled in different studies conducted in Africa, Europe, and North America. Volunteers ranged in age from 9 to 103 years. They also evaluated participants in the Framingham Heart Study, a long-term effort to identify common factors and characteristics that contribute to cardiovascular disease.

To examine people with a wide range of health challenges and associated stresses on their immune systems, the team also included participants who had influenza or COVID-19, and people living with HIV. They also included kidney transplant recipients, people with lifestyle factors that put them at high risk for sexually transmitted infections, and people who’d had sepsis, a condition in which the body has an extreme and life-threatening response following an infection.

The question in all these contexts was the same: How well did the two metrics of immune resilience predict an individual’s health outcomes and lifespan? The short answer is that immune resilience, longevity, and better health outcomes tracked together well. Those with metrics indicating optimal immune resilience generally had better health outcomes and lived longer than those who had lower scores on the immunity grading scale. Indeed, those with optimal immune resilience were more likely to:

- Live longer,

- Resist HIV infection or the progression from HIV to AIDS,

- Resist symptomatic influenza,

- Resist a recurrence of skin cancer after a kidney transplant,

- Survive COVID-19, and

- Survive sepsis.

The study also revealed other interesting findings. While immune resilience generally declines with age, some people maintain higher levels of immune resilience as they get older for reasons that aren’t yet known, according to the researchers. Some people also maintain higher levels of immune resilience despite the presence of inflammatory stress to their immune systems such as during HIV infection or acute COVID-19. People of all ages can show high or low immune resilience. The study also found that higher immune resilience is more common in females than it is in males.

The findings suggest that there is a lot more to learn about why people differ in their ability to preserve optimal immune resilience. With further research, it may be possible to develop treatments or other methods to encourage or restore immune resilience as a way of improving general health, according to the study team.

The researchers suggest it’s possible that one day checkups of a person’s immune resilience could help us to understand and predict an individual’s health status and risk for a wide range of health conditions. It could also help to identify those individuals who may be at a higher risk of poor outcomes when they do get sick and may need more aggressive treatment. Researchers may also consider immune resilience when designing vaccine clinical trials.

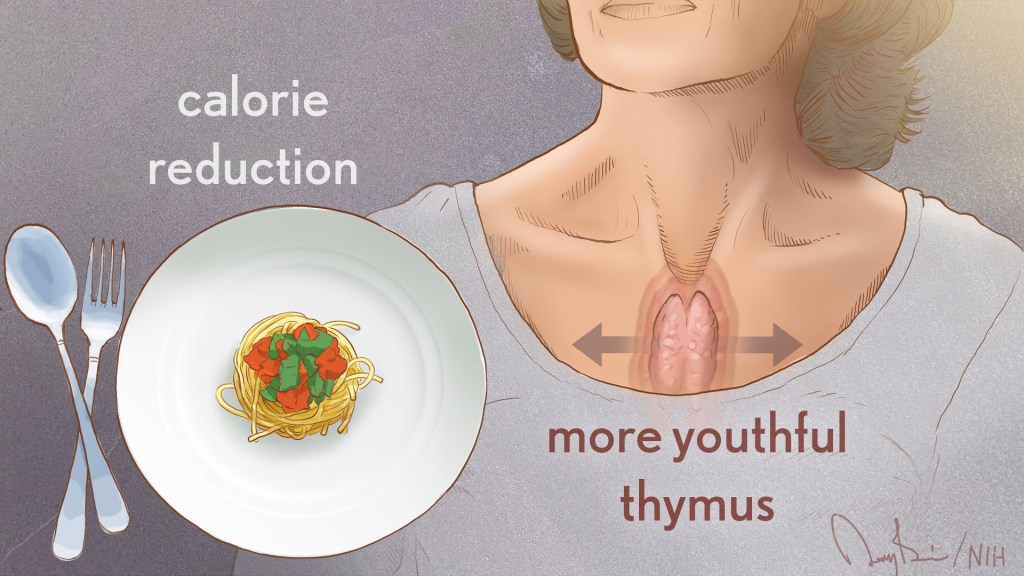

A more thorough understanding of immune resilience and discovery of ways to improve it may help to address important health disparities linked to differences in race, ethnicity, geography, and other factors. We know that healthy eating, exercising, and taking precautions to avoid getting sick foster good health and longevity; in the future, perhaps we’ll also consider how our immune resilience measures up and take steps to achieve or maintain a healthier, more balanced, immunity status.

References:

[1] Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection. Ahuja SK, Manoharan MS, Lee GC, McKinnon LR, Meunier JA, Steri M, Harper N, Fiorillo E, Smith AM, Restrepo MI, Branum AP, Bottomley MJ, Orrù V, Jimenez F, Carrillo A, Pandranki L, Winter CA, Winter LA, Gaitan AA, Moreira AG, Walter EA, Silvestri G, King CL, Zheng YT, Zheng HY, Kimani J, Blake Ball T, Plummer FA, Fowke KR, Harden PN, Wood KJ, Ferris MT, Lund JM, Heise MT, Garrett N, Canady KR, Abdool Karim SS, Little SJ, Gianella S, Smith DM, Letendre S, Richman DD, Cucca F, Trinh H, Sanchez-Reilly S, Hecht JM, Cadena Zuluaga JA, Anzueto A, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 team; Agan BK, Root-Bernstein R, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, He W. Nat Commun. 2023 Jun 13;14(1):3286. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38238-6. PMID: 37311745.

[2] Immunologic resilience and COVID-19 survival advantage. Lee GC, Restrepo MI, Harper N, Manoharan MS, Smith AM, Meunier JA, Sanchez-Reilly S, Ehsan A, Branum AP, Winter C, Winter L, Jimenez F, Pandranki L, Carrillo A, Perez GL, Anzueto A, Trinh H, Lee M, Hecht JM, Martinez-Vargas C, Sehgal RT, Cadena J, Walter EA, Oakman K, Benavides R, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 Team; Letendre S, Steri M, Orrù V, Fiorillo E, Cucca F, Moreira AG, Zhang N, Leadbetter E, Agan BK, Richman DD, He W, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, Ahuja SK. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Nov;148(5):1176-1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.021. Epub 2021 Sep 8. PMID: 34508765; PMCID: PMC8425719.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

HIV Info (NIH)

Sepsis (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Sunil Ahuja (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio)

Framingham Heart Study (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

“A Secret to Health and Long Life? Immune Resilience, NIAID Grantees Report,” NIAID Now Blog, June 13, 2023

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Encouraging First-in-Human Results for a Promising HIV Vaccine

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

In recent years, we’ve witnessed some truly inspiring progress in vaccine development. That includes the mRNA vaccines that were so critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, the first approved vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and a “universal flu vaccine” candidate that could one day help to thwart future outbreaks of more novel influenza viruses.

Inspiring progress also continues to be made toward a safe and effective vaccine for HIV, which still infects about 1.5 million people around the world each year [1]. A prime example is the recent first-in-human trial of an HIV vaccine made in the lab from a unique protein nanoparticle, a molecular construct measuring just a few billionths of a meter.

The results of this early phase clinical study, published recently in the journal Science Translational Medicine [2] and earlier in Science [3], showed that the experimental HIV nanoparticle vaccine is safe in people. While this vaccine alone will not offer HIV protection and is intended to be part of an eventual broader, multistep vaccination regimen, the researchers also determined that it elicited a robust immune response in nearly all 36 healthy adult volunteers.

How robust? The results show that the nanoparticle vaccine, known by the lab name eOD-GT8 60-mer, successfully expanded production of a rare type of antibody-producing immune B cell in nearly all recipients.

What makes this rare type of B cell so critical is that it is the cellular precursor of other B cells capable of producing broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) to protect against diverse HIV variants. Also very good news, the vaccine elicited broad responses from helper T cells. They play a critical supportive role for those essential B cells and their development of the needed broadly neutralizing antibodies.

For decades, researchers have brought a wealth of ideas to bear on developing a safe and effective HIV vaccine. However, crossing the finish line—an FDA-approved vaccine—has proved profoundly difficult.

A major reason is the human immune system is ill equipped to recognize HIV and produce the needed infection-fighting antibodies. And yet the medical literature includes reports of people with HIV who have produced the needed antibodies, showing that our immune system can do it.

But these people remain relatively rare, and the needed robust immunity clocks in only after many years of infection. On top of that, HIV has a habit of mutating rapidly to produce a wide range of identity-altering variants. For a vaccine to work, it most likely will need to induce the production of bnAbs that recognize and defend against not one, but the many different faces of HIV.

To make the uncommon more common became the quest of a research team that includes scientists William Schief, Scripps Research and IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center, La Jolla, CA; M. Juliana McElrath, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle; and Kristen Cohen, a former member of the McElrath lab now at Moderna, Cambridge, MA. The team, with NIH collaborators and support, has been plotting out a stepwise approach to train the immune system into making the needed bnAbs that recognize many HIV variants.

The critical first step is to prime the immune system to make more of those coveted bnAb-precursor B cells. That’s where the protein nanoparticle known as eOD-GT8 60-mer enters the picture.

This nanoparticle, administered by injection, is designed to mimic a small, highly conserved segment of an HIV protein that allows the virus to bind and infect human cells. In the body, those nanoparticles launch an immune response and then quickly vanish. But because this important protein target for HIV vaccines is so tiny, its signal needed amplification for immune system detection.

To boost the signal, the researchers started with a bacterial protein called lumazine synthase (LumSyn). It forms the scaffold, or structural support, of the self-assembling nanoparticle. Then, they added to the LumSyn scaffold 60 copies of the key HIV protein. This louder HIV signal is tailored to draw out and engage those very specific B cells with the potential to produce bnAbs.

As the first-in-human study showed, the nanoparticle vaccine was safe when administered twice to each participant eight weeks apart. People reported only mild to moderate side effects that went away in a day or two. The vaccine also boosted production of the desired B cells in all but one vaccine recipient (35 of 36). The idea is that this increase in essential B cells sets the stage for the needed additional steps—booster shots that can further coax these cells along toward making HIV protective bnAbs.

The latest finding in Science Translational Medicine looked deeper into the response of helper T cells in the same trial volunteers. Again, the results appear very encouraging. The researchers observed CD4 T cells specific to the HIV protein and to the LumSyn in 84 percent and 93 percent of vaccine recipients. Their analyses also identified key hotspots that the T cells recognized, which is important information for refining future vaccines to elicit helper T cells.

The team reports that they’re now collaborating with Moderna, the developer of one of the two successful mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, on an mRNA version of eOD-GT8 60-mer. That’s exciting because mRNA vaccines are much faster and easier to produce and modify, which should now help to move this line of research along at a faster clip.

Indeed, two International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI)-sponsored clinical trials of the mRNA version are already underway, one in the U.S. and the other in Rwanda and South Africa [4]. It looks like this team and others are now on a promising track toward following the basic science and developing a multistep HIV vaccination regimen that guides the immune response and its stepwise phases in the right directions.

As we look back on more than 40 years of HIV research, it’s heartening to witness the progress that continues toward ending the HIV epidemic. This includes the recent FDA approval of the drug Apretude, the first injectable treatment option for pre-exposure prevention of HIV, and the continued global commitment to produce a safe and effective vaccine.

References:

[1] Global HIV & AIDS statistics fact sheet. UNAIDS.

[2] A first-in-human germline-targeting HIV nanoparticle vaccine induced broad and publicly targeted helper T cell responses. Cohen KW, De Rosa SC, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Fiore-Gartland A, Laufer DS, Koup RA, McDermott AB, Schief WR, McElrath MJ. Sci Transl Med. 2023 May 24;15(697):eadf3309.

[3] Vaccination induces HIV broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in humans. Leggat DJ, Cohen KW, Willis JR, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Koup RA, Laufer DS, McElrath MJ, McDermott AB, Schief WR. Science. 2022 Dec 2;378(6623):eadd6502.

[4] IAVI and Moderna launch first-in-Africa clinical trial of mRNA HIV vaccine development program. IAVI. May 18, 2022.

Links:

Progress Toward an Eventual HIV Vaccine, NIH Research Matters, Dec. 13, 2022.

NIH Statement on HIV Vaccine Awareness Day 2023, Auchincloss H, Kapogiannis, B. May, 18, 2023.

HIV Vaccine Development (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) (New York, NY)

William Schief (Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA)

Julie McElrath (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

McElrath Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

A More Precise Way to Knock Out Skin Rashes

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

The NIH is committed to building a new era in medicine in which the delivery of health care is tailored specifically to the individual person, not the hypothetical average patient as is now often the case. This new era of “precision medicine” will transform care for many life-threatening diseases, including cancer and chronic kidney disease. But what about non-life-threatening conditions, like the aggravating rash on your skin that just won’t go away?

Recently, researchers published a proof-of-principle paper in the journal Science Immunology demonstrating just how precision medicine for inflammatory skin rashes might work [1]. While more research is needed to build out and further refine the approach, the researchers show it’s now technologically possible to extract immune cells from a patient’s rash, read each cell’s exact inflammatory features, and relatively quickly match them online to the right anti-inflammatory treatment to stop the rash.

The work comes from a NIH-funded team led by Jeffrey Cheng and Raymond Cho, University of California, San Francisco. The researchers focused their attention on two inflammatory skin conditions: atopic dermatitis, the most common type of eczema, which flares up periodically to make skin red and itchy, and psoriasis vulgaris. Psoriasis causes skin cells to build up and form a scaly rash and dry, itchy patches. Together, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis vulgaris affect about 10 percent of U.S. adults.

While the rashes caused by the two conditions can sometimes look similar, they are driven by different sets of immune cells and underlying inflammatory responses. For that reason, distinct biologic therapies, based on antibodies and proteins made from living cells, are now available to target and modify the specific immune pathways underlying each condition.

While biologic therapies represent a major treatment advance for these and other inflammatory conditions, they can miss their targets. Indeed, up to half of patients don’t improve substantially on biologics. Part of the reason for that lack of improvement is because doctors don’t have the tools they need to make firm diagnoses based on what precisely is going on in the skin at the molecular and cellular levels.

To learn more in the new study, the researchers isolated immune cells, focusing primarily on T cells, from the skin of 31 volunteers. They then sequenced the RNA of each cell to provide a telltale portrait of its genomic features. This “single-cell analysis” allowed them to capture high-resolution portraits of 41 different immune cell types found in individual skin samples. That’s important because it offers a much more detailed understanding of changes in the behavior of various immune cells that might have been missed in studies focused on larger groupings of skin cells, representing mixtures of various cell types.

Of the 31 volunteers, seven had atopic dermatitis and eight had psoriasis vulgaris. Three others were diagnosed with other skin conditions, while six had an indeterminate rash with features of both atopic dermatitis and psoriasis vulgaris. Seven others were healthy controls.

The team produced molecular signatures of the immune cells. The researchers then compared the signatures from the hard-to-diagnose rashes to those of confirmed cases of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. They wanted to see if the signatures could help to reach clearer diagnoses.

The signatures revealed common immunological features as well as underlying differences. Importantly, the researchers found that the signatures allowed them to move forward and classify the indeterminate rashes. The rashes also responded to biologic therapies corresponding to the individuals’ new diagnoses.

Already, the work has identified molecules that help to define major classes of human inflammatory skin diseases. The team has also developed computer tools to help classify rashes in many other cases where the diagnosis is otherwise uncertain.

In fact, the researchers have launched a pioneering website called RashX. It is enabling practicing dermatologists and researchers around the world to submit their single-cell RNA data from their difficult cases. Such analyses are now being done at a small, but growing, number of academic medical centers.

While precision medicine for skin rashes has a long way to go yet before reaching most clinics, the UCSF team is working diligently to ensure its arrival as soon as scientifically possible. Indeed, their new data represent the beginnings of an openly available inflammatory skin disease resource. They ultimately hope to generate a standardized framework to link molecular features to disease prognosis and drug response based on data collected from clinical centers worldwide. It’s a major effort, but one that promises to improve the diagnosis and treatment of many more unusual and long-lasting rashes, both now and into the future.

Reference:

[1] Classification of human chronic inflammatory skin disease based on single-cell immune profiling. Liu Y, Wang H, Taylor M, Cook C, Martínez-Berdeja A, North JP, Harirchian P, Hailer AA, Zhao Z, Ghadially R, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Grekin RC, Mauro TM, Kim E, Choi J, Purdom E, Cho RJ, Cheng JB. Sci Immunol. 2022 Apr 15;7(70):eabl9165. {Epub ahead of publication]

Links:

The Promise of Precision Medicine (NIH)

Atopic Dermatitis (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases /NIH)

Psoriasis (NIAMS/NIH)

RashX (University of California, San Francisco)

Raymond Cho (UCSF)

Jeffrey Cheng (UCSF)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Latest on Omicron Variant and COVID-19 Vaccine Protection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s been great concern about the new Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. A major reason is Omicron has accumulated over 50 mutations, including about 30 in the spike protein, the part of the coronavirus that mRNA vaccines teach our immune systems to attack. All of these genetic changes raise the possibility that Omicron could cause breakthrough infections in people who’ve already received a Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccine.

So, what does the science show? The first data to emerge present somewhat encouraging results. While our existing mRNA vaccines still offer some protection against Omicron, there appears to be a significant decline in neutralizing antibodies against this variant in people who have received two shots of an mRNA vaccine.

However, initial results of studies conducted both in the lab and in the real world show that people who get a booster shot, or third dose of vaccine, may be better protected. Though these data are preliminary, they suggest that getting a booster will help protect people already vaccinated from breakthrough or possible severe infections with Omicron during the winter months.

Though Omicron was discovered in South Africa only last month, researchers have been working around the clock to learn more about this variant. Last week brought the first wave of scientific data on Omicron, including interesting work from a research team led by Alex Sigal, Africa Health Research Institute, Durban, South Africa [1].

In lab studies working with live Omicron virus, the researchers showed that this variant still relies on the ACE2 receptor to infect human lung cells. That’s really good news. It means that the therapeutic tools already developed, including vaccines, should generally remain useful for combatting this new variant.

Sigal and colleagues also tested the ability of antibodies in the plasma from 12 fully vaccinated individuals to neutralize Omicron. Six of the individuals had no history of COVID-19. The other six had been infected with the original variant in the first wave of infections in South Africa.

As expected, the samples showed very strong neutralization against the original SARS-CoV-2 variant. However, antibodies from people who’d been previously vaccinated with the two-dose Pfizer vaccine took a significant hit against Omicron, showing about a 40-fold decline in neutralizing ability.

This escape from immunity wasn’t complete. Indeed, blood samples from five individuals showed relatively good antibody levels against Omicron. All five had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2 in addition to being vaccinated. These findings add to evidence on the value of full vaccination for protecting against reinfections in people who’ve had COVID-19 previously.

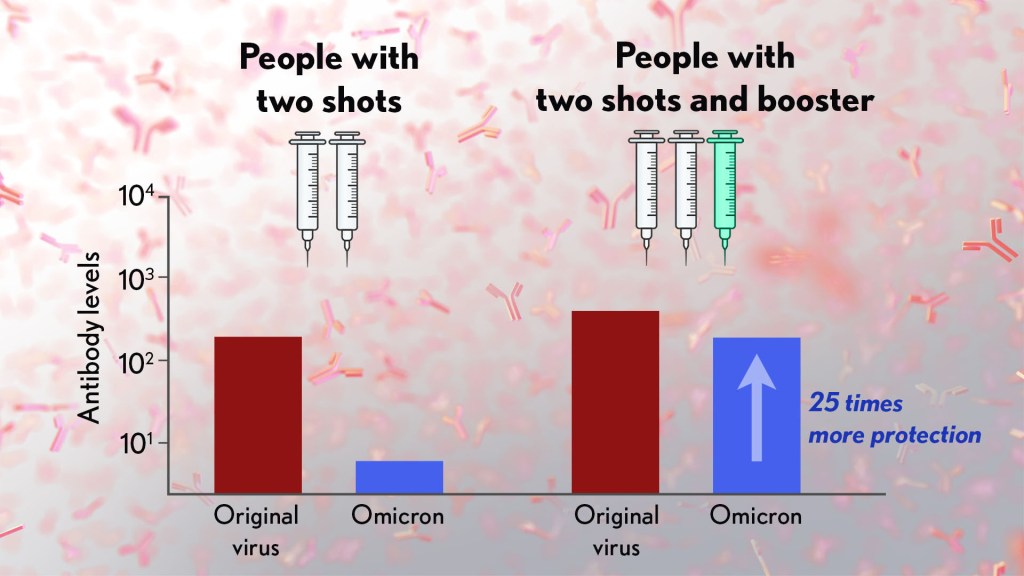

Also of great interest were the first results of the Pfizer study, which the company made available in a news release [2]. Pfizer researchers also conducted laboratory studies to test the neutralizing ability of blood samples from 19 individuals one month after a second shot compared to 20 others one month after a booster shot.

These studies showed that the neutralizing ability of samples from those who’d received two shots had a more than 25-fold decline relative to the original virus. Together with the South Africa data, it suggests that the two-dose series may not be enough to protect against breakthrough infections with the Omicron variant.

In much more encouraging news, their studies went on to show that a booster dose of the Pfizer vaccine raised antibody levels against Omicron to a level comparable to the two-dose regimen against the original variant (as shown in the figure above). While efforts already are underway to develop an Omicron-specific COVID-19 vaccine, these findings suggest that it’s already possible to get good protection against this new variant by getting a booster shot.

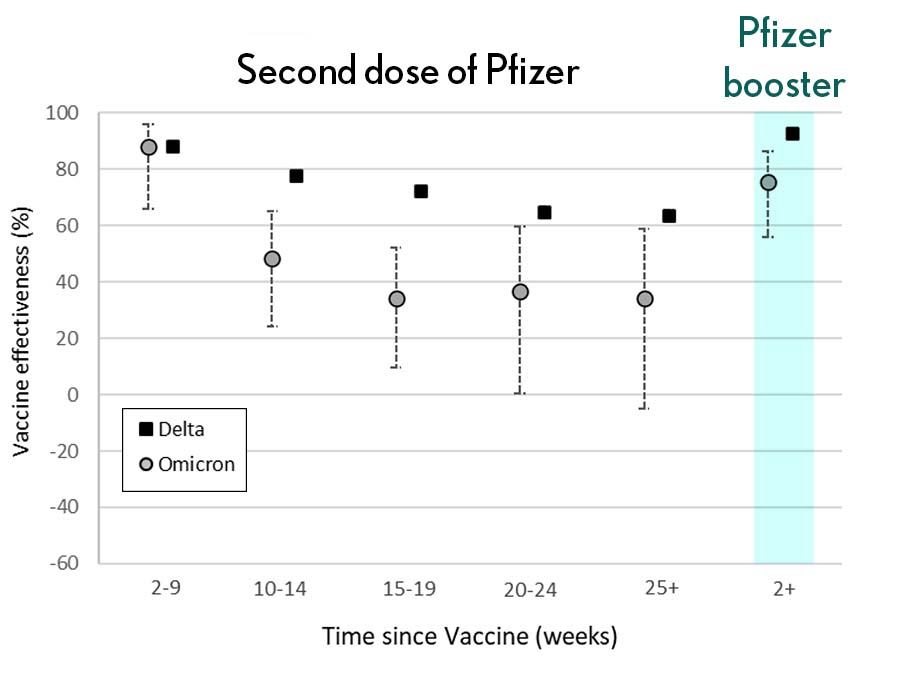

Very recently, real-world data from the United Kingdom, where Omicron cases are rising rapidly, are providing additional evidence for how boosters can help. In a preprint [3], Andrews et. al showed the effectiveness of two shots of Pfizer mRNA vaccine trended down after four months to about 40 percent. That’s not great, but note that 40 percent is far better than zero. So, clearly there is some protection provided.

Most impressively (as shown in the figure from Andrews N, et al.) a booster substantially raised that vaccine effectiveness to about 80 percent. That’s not quite as high as for Delta, but certainly an encouraging result. Once again, these data show that boosting the immune system after a pause produces enhanced immunity against new viral variants, even though the booster was designed from the original virus. Your immune system is awfully clever. You get both quantitative and qualitative benefits.

It’s also worth noting that the Omicron variant mostly doesn’t have mutations in portions of its genome that are the targets of other aspects of vaccine-induced immunity, including T cells. These cells are part of the body’s second line of defense and are generally harder for viruses to escape. While T cells can’t prevent infection, they help protect against more severe illness and death.

It’s important to note that scientists around the world are also closely monitoring Omicron’s severity While this variant appears to be highly transmissible, and it is still early for rigorous conclusions, the initial research indicates this variant may actually produce milder illness than Delta, which is currently the dominant strain in the United States.

But there’s still a tremendous amount of research to be done that could change how we view Omicron. This research will take time and patience.

What won’t change, though, is that vaccines are the best way to protect yourself and others against COVID-19. (And these recent data provide an even-stronger reason to get a booster now if you are eligible.) Wearing a mask, especially in public indoor settings, offers good protection against the spread of all SARS-CoV-2 variants. If you’ve got symptoms or think you may have been exposed, get tested and stay home if you get a positive result. As we await more answers, it’s as important as ever to use all the tools available to keep yourself, your loved ones, and your community happy and healthy this holiday season.

References:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 Omicron has extensive but incomplete escape of Pfizer BNT162b2 elicited neutralization and requires ACE2 for infection. Sandile C, et al. Sandile C, et al. medRxiv preprint. December 9, 2021.

[2] Pfizer and BioNTech provide update on Omicron variant. Pfizer. December 8, 2021.

[3] Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant of concern. Andrews N, et al. KHub.net preprint. December 10, 2021.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Sigal Lab (Africa Health Research Institute, Durban, South Africa)

Teaching the Immune System to Attack Cancer with Greater Precision

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

To protect humans from COVID-19, the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines program human cells to translate the injected synthetic messenger RNA into the coronavirus spike protein, which then primes the immune system to arm itself against future appearances of that protein. It turns out that the immune system can also be trained to spot and attack distinctive proteins on cancer cells, killing them and leaving healthy cells potentially untouched.

While these precision cancer vaccines remain experimental, researchers continue to make basic discoveries that move the field forward. That includes a recent NIH-funded study in mice that helps to refine the selection of protein targets on tumors as a way to boost the immune response [1]. To enable this boost, the researchers first had to discover a possible solution to a longstanding challenge in developing precision cancer vaccines: T cell exhaustion.

The term refers to the immune system’s complement of T cells and their capacity to learn to recognize foreign proteins, also known as neoantigens, and attack them on cancer cells to shrink tumors. But these responding T cells can exhaust themselves attacking tumors, limiting the immune response and making its benefits short-lived.

In this latest study, published in the journal Cell, Tyler Jacks and Megan Burger, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, help to explain this phenomenon of T cell exhaustion. The researchers found in mice with lung tumors that the immune system initially responds as it should. It produces lots of T cells that target many different cancer-specific proteins.

Yet there’s a problem: various subsets of T cells get in each other’s way. They compete until, eventually, one of those subsets becomes the dominant T cell type. Even when those dominant T cells grow exhausted, they still remain in the tumor and keep out other T cells, which might otherwise attack different neoantigens in the cancer.

Building on this basic discovery, the researchers came up with a strategy for developing cancer vaccines that can “awaken” T cells and reinvigorate the body’s natural cancer-fighting abilities. The strategy might seem counterintuitive. The researchers vaccinated mice with neoantigens that provide a weak but encouraging signal to the immune cells responsible for presenting the distinctive cancer protein target, or antigen, to T cells. It’s those T cells that tend to get suppressed in competition with other T cells.

When the researchers vaccinated the mice with one of those neoantigens, the otherwise suppressed T cells grew in numbers and better targeted the tumor. What’s more, the tumors shrank by more than 25 percent on average.

Research on this new strategy remains in its early stages. The researchers hope to learn if this approach to cancer vaccines might work even better when used in combination with immunotherapy drugs, which unleash the immune system against cancer in other ways.

It’s also possible that the recent and revolutionary success of mRNA vaccines for preventing COVID-19 actually could help. An important advantage of mRNA is that it’s easy for researchers to synthesize once they know the specific nucleic acid sequence of a protein target, and they can even combine different mRNA sequences to make a multiplex vaccine that primes the immune system to recognize multiple neoantigens. Now that we’ve seen how well mRNA vaccines work to prompt a desired immune response against COVID-19, this same technology can be used to speed the development and testing of future vaccines, including those designed precisely to fight cancer.

Reference:

[1] Antigen dominance hierarchies shape TCF1+ progenitor CD8 T cell phenotypes in tumors. Burger ML, Cruz AM, Crossland GE, Gaglia G, Ritch CC, Blatt SE, Bhutkar A, Canner D, Kienka T, Tavana SZ, Barandiaran AL, Garmilla A, Schenkel JM, Hillman M, de Los Rios Kobara I, Li A, Jaeger AM, Hwang WL, Westcott PMK, Manos MP, Holovatska MM, Hodi FS, Regev A, Santagata S, Jacks T. Cell. 2021 Sep 16;184(19):4996-5014.e26.

Links:

Cancer Treatment Vaccines (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

The Jacks Lab (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Studies Confirm COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines Safe, Effective for Pregnant Women

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Clinical trials have shown that COVID-19 vaccines are remarkably effective in protecting those age 12 and up against infection by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The expectation was that they would work just as well to protect pregnant women. But because pregnant women were excluded from the initial clinical trials, hard data on their safety and efficacy in this important group has been limited.

So, I’m pleased to report results from two new studies showing that the two COVID-19 mRNA vaccines now available in the United States appear to be completely safe for pregnant women. The women had good responses to the vaccines, producing needed levels of neutralizing antibodies and immune cells known as memory T cells, which may offer more lasting protection. The research also indicates that the vaccines might offer protection to infants born to vaccinated mothers.

In one study, published in JAMA [1], an NIH-supported team led by Dan Barouch, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, wanted to learn whether vaccines would protect mother and baby. To find out, they enrolled 103 women, aged 18 to 45, who chose to get either the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccines from December 2020 through March 2021.

The sample included 30 pregnant women,16 women who were breastfeeding, and 57 women who were neither pregnant nor breastfeeding. Pregnant women in the study got their first dose of vaccine during any trimester, although most got their shots in the second or third trimester. Overall, the vaccine was well tolerated, although some women in each group developed a transient fever after the second vaccine dose, a common side effect in all groups that have been studied.

After vaccination, women in all groups produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, those antibodies neutralized SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. The researchers also found those antibodies in infant cord blood and breast milk, suggesting that they were passed on to afford some protection to infants early in life.

The other NIH-supported study, published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology, was conducted by a team led by Jeffery Goldstein, Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago [2]. To explore any possible safety concerns for pregnant women, the team took a first look for any negative effects of vaccination on the placenta, the vital organ that sustains the fetus during gestation.

The researchers detected no signs that the vaccines led to any unexpected damage to the placenta in this study, which included 84 women who received COVID-19 mRNA vaccines during pregnancy, most in the third trimester. As in the other study, the team found that vaccinated pregnant women showed a robust response to the vaccine, producing needed levels of neutralizing antibodies.

Overall, both studies show that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines are safe and effective in pregnancy, with the potential to benefit both mother and baby. Pregnant women also are more likely than women who aren’t pregnant to become severely ill should they become infected with this devastating coronavirus [3]. While pregnant women are urged to consult with their obstetrician about vaccination, growing evidence suggests that the best way for women during pregnancy or while breastfeeding to protect themselves and their families against COVID-19 is to roll up their sleeves and get either one of the mRNA vaccines now authorized for emergency use.

References:

[1] Immunogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in pregnant and lactating women. Collier AY, McMahan K, Yu J, Tostanoski LH, Aguayo R, Ansel J, Chandrashekar A, Patel S, Apraku Bondzie E, Sellers D, Barrett J, Sanborn O, Wan H, Chang A, Anioke T, Nkolola J, Bradshaw C, Jacob-Dolan C, Feldman J, Gebre M, Borducchi EN, Liu J, Schmidt AG, Suscovich T, Linde C, Alter G, Hacker MR, Barouch DH. JAMA. 2021 May 13.

[2] Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccination in pregnancy: Measures of immunity and placental histopathology. Shanes ED, Otero S, Mithal LB, Mupanomunda CA, Miller ES, Goldstein JA. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 May 11.

[3] COVID-19 vaccines while pregnant or breastfeeding. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Barouch Laboratory (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Jeffery Goldstein (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

The People’s Picks for Best Posts

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s 2021—Happy New Year! Time sure flies in the blogosphere. It seems like just yesterday that I started the NIH Director’s Blog to highlight recent advances in biology and medicine, many supported by NIH. Yet it turns out that more than eight years have passed since this blog got rolling and we are fast approaching my 1,000th post!

I’m pleased that millions of you have clicked on these posts to check out some very cool science and learn more about NIH and its mission. Thanks to the wonders of social media software, we’ve been able to tally up those views to determine each year’s most-popular post. So, I thought it would be fun to ring in the New Year by looking back at a few of your favorites, sort of a geeky version of a top 10 countdown or the People’s Choice Awards. It was interesting to see what topics generated the greatest interest. Spoiler alert: diet and exercise seemed to matter a lot! So, without further ado, I present the winners:

2013: Fighting Obesity: New Hopes from Brown Fat. Brown fat, one of several types of fat made by our bodies, was long thought to produce body heat rather than store energy. But Shingo Kajimura and his team at the University of California, San Francisco, showed in a study published in the journal Nature, that brown fat does more than that. They discovered a gene that acts as a molecular switch to produce brown fat, then linked mutations in this gene to obesity in humans.

What was also nice about this blog post is that it appeared just after Kajimura had started his own lab. In fact, this was one of the lab’s first publications. One of my goals when starting the blog was to feature young researchers, and this work certainly deserved the attention it got from blog readers. Since highlighting this work, research on brown fat has continued to progress, with new evidence in humans suggesting that brown fat is an effective target to improve glucose homeostasis.

2014: In Memory of Sam Berns. I wrote this blog post as a tribute to someone who will always be very near and dear to me. Sam Berns was born with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, one of the rarest of rare diseases. After receiving the sad news that this brave young man had passed away, I wrote: “Sam may have only lived 17 years, but in his short life he taught the rest of us a lot about how to live.”

Affecting approximately 400 people worldwide, progeria causes premature aging. Without treatment, children with progeria, who have completely normal intellectual development, die of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, on average in their early teens.

From interactions with Sam and his parents in the early 2000s, I started to study progeria in my NIH lab, eventually identifying the gene responsible for the disorder. My group and others have learned a lot since then. So, it was heartening last November when the Food and Drug Administration approved the first treatment for progeria. It’s an oral medication called Zokinvy (lonafarnib) that helps prevent the buildup of defective protein that has deadly consequences. In clinical trials, the drug increased the average survival time of those with progeria by more than two years. It’s a good beginning, but we have much more work to do in the memory of Sam and to help others with progeria. Watch for more about new developments in applying gene editing to progeria in the next few days.

2015: Cytotoxic T Cells on Patrol. Readers absolutely loved this post. When the American Society of Cell Biology held its first annual video competition, called CellDance, my blog featured some of the winners. Among them was this captivating video from Alex Ritter, then working with cell biologist Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz of NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The video stars a roving, specialized component of our immune system called cytotoxic T cells. Their job is to seek out and destroy any foreign or detrimental cells. Here, these T cells literally convince a problem cell to commit suicide, a process that takes about 10 minutes from detection to death.

These cytotoxic T cells are critical players in cancer immunotherapy, in which a patient’s own immune system is enlisted to control and, in some cases, even cure the cancer. Cancer immunotherapy remains a promising area of research that continues to progress, with a lot of attention now being focused on developing immunotherapies for common, solid tumors like breast cancer. Ritter is currently completing a postdoctoral fellowship in the laboratory of Ira Mellman, Genentech, South San Francisco. His focus has shifted to how cancer cells protect themselves from T cells. And video buffs—get this—Ritter says he’s now created even cooler videos that than the one in this post.

2016: Exercise Releases Brain-Healthy Protein. The research literature is pretty clear: exercise is good for the brain. In this very popular post, researchers led by Hyo Youl Moon and Henriette van Praag of NIH’s National Institute on Aging identified a protein secreted by skeletal muscle cells to help explore the muscle-brain connection. In a study in Cell Metabolism, Moon and his team showed that this protein called cathepsin B makes its way into the brain and after a good workout influences the development of new neural connections. This post is also memorable to me for the photo collage that accompanied the original post. Why? If you look closely at the bottom right, you’ll see me exercising—part of my regular morning routine!

2017: Muscle Enzyme Explains Weight Gain in Middle Age. The struggle to maintain a healthy weight is a lifelong challenge for many of us. While several risk factors for weight gain, such as counting calories, are within our control, there’s a major one that isn’t: age. Jay Chung, a researcher with NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and his team discovered that the normal aging process causes levels of an enzyme called DNA-PK to rise in animals as they approach middle age. While the enzyme is known for its role in DNA repair, their studies showed it also slows down metabolism, making it more difficult to burn fat.

Since publishing this paper in Cell Metabolism, Chung has been busy trying to understand how aging increases the activity of DNA-PK and its ability to suppress renewal of the cell’s energy-producing mitochondria. Without renewal of damaged mitochondria, excess oxidants accumulate in cells that then activate DNA-PK, which contributed to the damage in the first place. Chung calls it a “vicious cycle” of aging and one that we’ll be learning more about in the future.

2018: Has an Alternative to Table Sugar Contributed to the C. Diff. Epidemic? This impressive bit of microbial detective work had blog readers clicking and commenting for several weeks. So, it’s no surprise that it was the runaway People’s Choice of 2018.

Clostridium difficile (C. diff) is a common bacterium that lives harmlessly in the gut of most people. But taking antibiotics can upset the normal balance of healthy gut microbes, allowing C. diff. to multiply and produce toxins that cause inflammation and diarrhea.

In the 2000s, C. diff. infections became far more serious and common in American hospitals, and Robert Britton, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wanted to know why. He and his team discovered that two subtypes of C. diff have adapted to feed on the sugar trehalose, which was approved as a food additive in the United States during the early 2000s. The team’s findings, published in the journal Nature, suggested that hospitals and nursing homes battling C. diff. outbreaks may want to take a closer look at the effect of trehalose in the diet of their patients.

2019: Study Finds No Benefit for Dietary Supplements. This post that was another one that sparked a firestorm of comments from readers. A team of NIH-supported researchers, led by Fang Fang Zhang, Tufts University, Boston, found that people who reported taking dietary supplements had about the same risk of dying as those who got their nutrients through food. What’s more, the mortality benefits associated with adequate intake of vitamin A, vitamin K, magnesium, zinc, and copper were limited to amounts that are available from food consumption. The researchers based their conclusion on an analysis of the well-known National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1999-2000 and 2009-2010 survey data. The team, which reported its data in the Annals of Internal Medicine, also uncovered some evidence suggesting that certain supplements might even be harmful to health when taken in excess.

2020: Genes, Blood Type Tied to Risk of Severe COVID-19. Typically, my blog focuses on research involving many different diseases. That changed in 2020 due to the emergence of a formidable public health challenge: the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Since last March, the blog has featured 85 posts on COVID-19, covering all aspects of the research response and attracting more visitors than ever. And which post got the most views? It was one that highlighted a study, published last June in the New England Journal of Medicine, that suggested the clues to people’s variable responses to COVID-19 may be found in our genes and our blood types.

The researchers found that gene variants in two regions of the human genome are associated with severe COVID-19 and correspondingly carry a greater risk of COVID-19-related death. The two stretches of DNA implicated as harboring risks for severe COVID-19 are known to carry some intriguing genes, including one that determines blood type and others that play various roles in the immune system.

In fact, the findings suggest that people with blood type A face a 50 percent greater risk of needing oxygen support or a ventilator should they become infected with the novel coronavirus. In contrast, people with blood type O appear to have about a 50 percent reduced risk of severe COVID-19.

That’s it for the blog’s year-by-year Top Hits. But wait! I’d also like to give shout outs to the People’s Choice winners in two other important categories—history and cool science images.

Top History Post: HeLa Cells: A New Chapter in An Enduring Story. Published in August 2013, this post remains one of the blog’s greatest hits with readers. The post highlights science’s use of cancer cells taken in the 1950s from a young Black woman named Henrietta Lacks. These “HeLa” cells had an amazing property not seen before: they could be grown continuously in laboratory conditions. The “new chapter” featured in this post is an agreement with the Lacks family that gives researchers access to the HeLa genome data, while still protecting the family’s privacy and recognizing their enormous contribution to medical research. And the acknowledgments rightfully keep coming from those who know this remarkable story, which has been chronicled in both book and film. Recently, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives passed the Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act to honor her extraordinary life and examine access to government-funded cancer clinical trials for traditionally underrepresented groups.

Top Snapshots of Life: A Close-up of COVID-19 in Lung Cells. My blog posts come in several categories. One that you may have noticed is “Snapshots of Life,” which provides a showcase for cool images that appear in scientific journals and often dominate Science as Art contests. My blog has published dozens of these eye-catching images, representing a broad spectrum of the biomedical sciences. But the blog People’s Choice goes to a very recent addition that reveals exactly what happens to cells in the human airway when they are infected with the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19. This vivid image, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, comes from the lab of pediatric pulmonologist Camille Ehre, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This image squeezed in just ahead of another highly popular post from Steve Ramirez, Boston University, in 2019 that showed “What a Memory Looks Like.”

As we look ahead to 2021, I want to thank each of my blog’s readers for your views and comments over the last eight years. I love to hear from you, so keep on clicking! I’m confident that 2021 will generate a lot more amazing and bloggable science, including even more progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic that made our past year so very challenging.

Next Page